Caveat

There are clear ‘connections between [development] finance, trade and investments, debt, and financial flows from the private sector’ (Saldinger 2024), which combine to produce a complex, interwoven picture of financing for sustainable development. Despite their entwined nature, the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) treats these issues as distinct action areas. As such, this Helpdesk Answer adopts the same approach.

This Helpdesk Answer draws extensively on previous work written by the same author (Jenkins 2018b, 2016a, 2024a, 2016b, 2022, 2018a, 2024b).

Query

Please provide an overview of why anti-corruption efforts matter to the financing for development agenda, with a particular focus on domestic and international private business, international development cooperation, international trade and debt sustainability.

Background

From huge infrastructure projects to climate change mitigation measures, the estimated cost to realise the full ambition of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is around US$5 trillion to US$7 trillion per year (Filho et al. 2022; OHCHR 2022; United Nations 2024). Recent estimates indicate that the gap between those needs and current levels of total development financing is between US$2.5 trillion to US$4 trillion annually (United Nations Economic and Social Council 2024: 2).

Financial resources to realise this aspirational agenda are drawn from a wide range of sources, both public and private, domestic and foreign. Financing for development (FfD) therefore involves governments, businesses and citizens mobilising, managing and disbursing a large array of funds, from those generated in-country, like taxation, to those originating abroad, such as development assistance, foreign investment and sovereign loans.

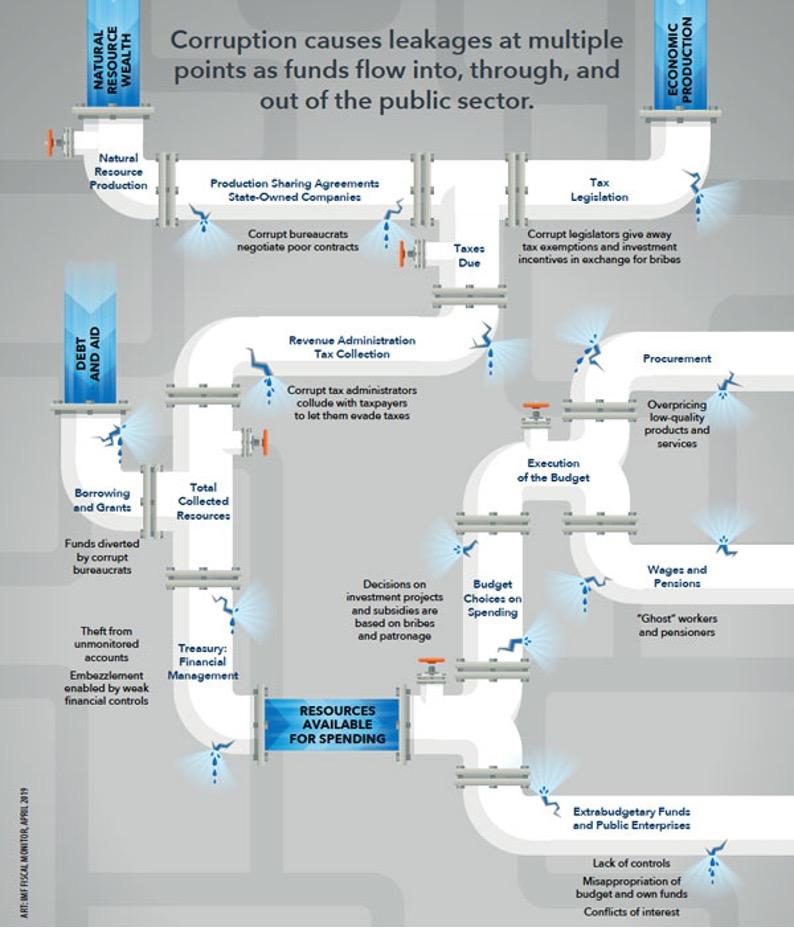

Yet corruption weakens the capability of societies to pay for the vast investments needed to meet the SDGs at every stage of the public financial management cycle (Figure 1). Corruption frustrates the effective mobilisation of finance for development in several ways, including by facilitating tax evasion and enabling the transfer of ill-gotten gains to overseas jurisdictions, thereby reducing the quantity of resources that governments are able or willing to collect (Alm, Martinez-Vazquez and McClellan 2016; Payne and Saunoris 2020). Forms of corruption such as undue influence and clientelism can distort the allocation of whatever development funds are raised, channelling them towards sectors and markets that serve a narrow interest group or offer opportunities for rent-seeking. Finally, venality, graft and embezzlement can undermine the efficient disbursement of development spending and thereby diminish the effectiveness of development initiatives.

Figure 1: Corruption across the public financial management system

Mauro, Medas and Fournier 2019.

As such, it has long been clear that corruption reduces the quantity and quality of developmental spending by governments, international donors and impact investors. In the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development world leaders recognised that, without measures to tackle ‘corruption and bribery in all their forms’, establishing peaceful, just and inclusive societies will not be possible and that progress towards other development goals will be fragmentary (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2024). This acknowledgement is reflected in the financial architecture designed and agreed by UN member states to support the 2030 Agenda; the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) describes measures to curb corruption as ‘central to enabling the effective, efficient and transparent mobilisation and use of resources’, alongside other variables such as human rights, rule of law, peace and security, and accountable institutions (United Nations 2015: 3).

Yet, to date, this commitment to counter corruption’s impact on the mobilisation and use of resources has been interpreted narrowly in financing for development outcome documents and interim reports published by the United Nations Economic and Social Council (2024) and the UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development (2023).

In these documents, consideration of the impacts of corruption on the Financing for Development agenda has largely been restricted to its role in hollowing out state coffers and diverting much-needed domestic public resources (Action Area 1). As such, the effect of corruption in frustrating the mobilisation and use of resources relating to other Action Areas set out in the AAAA is largely overlooked, including with regard to:

- Domestic and international private business and finance

- International development cooperation

- International trade as an engine for development

- Debt and debt sustainability

This is in spite of the fact that there is mounting evidence that corruption also erodes the ability of these channels to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs.

While the AAAA does not clearly delimit the scope of the action areas, it does provide some indication of the core policy issues related to each one. Taking these four action areas as points of departure, the following sections draw attention in italics to specific policy issues in each area mentioned in the text of the AAAA that the author of this paper has assessed to be particularly affected by corruption. Based on a survey of the literature, evidence on the relationship between corruption and these policy issues is then presented. As such, this Helpdesk Answer distils some high-level insights on how corruption:

- distorts the business environment and inhibits foreign direct investment

- reduces the positive impacts of official development assistance

- skews international trade to the disadvantage of low and middle-income countries and

- results in unsustainable borrowing practices.

Collectively, the evidence presented in this paper illustrates that corruption can be usefully understood as a cross-cutting issue across the whole Financing for Development agenda. This could provide a compelling case for anti-corruption instruments to be embedded into each Action Area. Indeed, this review of the literature suggests that domestic public resources cannot be fully shielded from corrupt abuses unless integrity risks relating to private investment, development assistance, international trade and opaque debt are addressed. Investment in anti-corruption measures could help ensure that more money is mobilised for development initiatives and more of that money reaches people and places where it can have a genuinely transformative positive impact.

This is increasingly recognised by the UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development (2023: 19), which observed in its 2022 report that corruption often impedes ‘financial resources and policies being effectively translated into desired development outcomes’, and control of corruption is an ‘important determinant of the long-term growth prospects of countries’. Other voices are also calling for greater attention to the issue of corruption in the next iteration of the financing for development framework, with one preparatory paper calling for the establishment of an anti-corruption ‘FfD working group bringing together engaged legal and financial authorities with civil society, legal and business organisations [to] build momentum toward support at the highest political levels’ (Herman 2022: 19).

Corruption’s effect on the business environment and investment climate

The AAAA framework lists ‘domestic and international private business and finance’ as one of its key action areas to guide international efforts to align all development financing flows and policies with the economic, social and environmental priorities set out in the 2030 Agenda.

The AAAA states that private sector activities, investments and innovations are key determinants of sustainable development as they drive ‘productivity, inclusive economic growth and job creation’ (United Nations 2015: 17). Foreign direct investment in particular is argued to be a ‘vital complement to national development efforts’ (United Nations 2015: 17). As such, governments are called on to create business environments that encourage all manner of commercial enterprises to contribute to sustainable development (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs 2015: 6). The AAAA stipulates that this requires ‘transparent, stable and predictable investment climates, with proper contract enforcement and respect for property rights, embedded in sound macroeconomic policies and institutions […] and free and fair competition’ (United Nations 2015: 18). Finally, the AAAA appeals to UN member states to promote impact investing and sustainable corporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices (United Nations 2015: 18).

Corruption, economic growth and the business environment

A large and growing body of research has evaluated the impact of corruption on economic growth and market competitiveness. It provides clear indication that, at the aggregate level, corruption is bad for business. The claim that corruption acts as a ‘grease in the wheels’ contributing to a country’s economic development by helping investors and entrepreneurs to circumvent red tape finds little empirical support. Indeed, as Stephenson (2021) puts it, corruption is far more often an ‘impediment’ than a ‘facilitator’ of economic growth.

The overwhelming consensus now is that high levels of corruption in a given country or market are harmful to business. First, rampant corruption damages a state’s ability to invest in infrastructure, produce a healthy and educated workforce, uphold law and order, provide impartial justice for commercial disputes and pursue sound macroeconomic policies, all of which matter immensely for economic development (Stephenson 2021; Farinha and López-de-Foronda 2024). A recent World Bank working paper identified a significant adverse empirical effect of administrative corruption on SMEs’ access to finance. The authors concluded that this is due to the effect of administrative corruption in ‘lowering profits, increasing credit demand, increasing bankruptcy chances, creating uncertainty about the firm’s future profit, and exacerbating the asymmetric information problem between borrowers and lenders’ (Amin and Motta 2021: 2).

Various other studies have demonstrated how corruption has adverse effects on a country’s economic performance by reducing institutional quality, undermining competitiveness and entrepreneurship, distorting the allocation of credit and acting as a barrier to trade (Ali and Mdhillat 2015; De Jong and Udo 2006; Horsewood and Voicu 2012; Musila and Sigué 2010; Rodrik, Subramanian, and Trebbi 2004; Zelekha and Sharabi 2012; De Jong and Bogmans 2011). Corrupt practices can thus skew the business environment, especially where politically connected firms are able to prevent potential competitors entering the market through policy or regulatory capture, as Rijkers, Freund and Nucifora (2017) show with regard to Tunisia.

The result is that, according to the weight of evidence, high levels of corruption are positively and significantly correlated with lower GDP per capita, less foreign investment and slower growth (Ades and Di Tella 1999; Alfada 2019; Anoruo and Braha 2005; Cieślik and Goczek 2018; Gründler and Potrafke 2019; Kaufmann and Wei 1999; Knack and Keefer 1995; Hall and Jones 1999; Javorcik and Wei 2009; Méndez and Sepúlveda 2006; Méon and Sekkat 2005; Oke and Onaolapo 2022; Rock and Bonnett 2004). Moreover, on average, enterprises operating in countries with high levels of background corruption have relatively lower firm performance than those operating in markets with lower risks of corruption (Donadelli and Persha 2014; Doh et al. 2003; Faruq, Webb and Yi 2013; Gray, Hellman and Ryterman 2004; Mauro 1995; Wieneke and Gries 2011). Empirical research has, for instance, found a significant negative correlation between levels of corruption in US states and the value of firms located in those states (Dass, Nanda and Xiao 2014).

Corruption’s impact on firm-level productivity and innovation

A sizeable number of researchers have examined the benefits and costs of engaging in bribery and other corrupt practices at the firm level, including the impact of corporate corruption on a firm’s profitability, sales, competitiveness, growth and staff morale. In terms the costs and benefits of corporate corruption for individual firms, most of the evidence suggests that the long-term (and often indirect) costs of corruption outweigh any short-term benefits (Athanasouli, Goujard, and Sklias 2012; De Rosa, Gooroochurn, and Görg 2010; Faruq, Webb, and Yi 2013; Gaviria 2002; McArthur and Teal 2002; Lavallée and Roubaud 2011), though there are some dissenting voices (Williams and Martinez-Perez 2016). This leads Nichols (2012: 329), in a systematic review of the field, to declare that ‘a very strong business case exists for complying with the rules regarding bribery’.

On balance, these studies find that corruption begets corruption; evidence suggests that where a firm gains a reputation for paying bribes, not only do demands multiply overtime from the original bribe-taker who uses the initial transgression as leverage to continue extracting rent (Wrage 2007; Almond and Syfert 1996) but other actors begin to demand bribes, incentivised to try and line their own pockets at the firm’s expense (Earle and Cava 2008; Krever 2007: 87). As such, firms with a propensity to pay bribes not only find themselves spending more time and money dealing with the bureaucracy but also suffering from the indirect costs such as lower productivity, slower growth, employee theft and more expensive access to capital.

Moreover, although some of the more indirect costs may not be captured on a company’s account books, they can have severe implications on the firm’s performance. Considering a sample of firms from sub-Saharan African countries, McArthur and Teal (2002) found that firms that pay bribes to public officials have 20% lower output per worker, while Faruq, Webb, and Yi (2013) observe a vicious cycle: not only are less productive firms more likely to turn to bribery but that this corruption further reduces firm productivity. Corrupt practices such as nepotism or patronage can result in contracting or recruitment processes being conducted on the basis of connections rather than merit, resulting in the hiring of incompetent employees or contractors who reduce a firm’s productivity (Ombanda 2018).

As such, at the firm level, corruption is likely to bring at best limited short-term gains at the expense of long-term performance, growth and productivity, even where the transgression is not detected. Where incidences of corruption are detected by regulators or law enforcement, the financial penalties and loss of investor confidence can cripple a firm.025b86008fc6

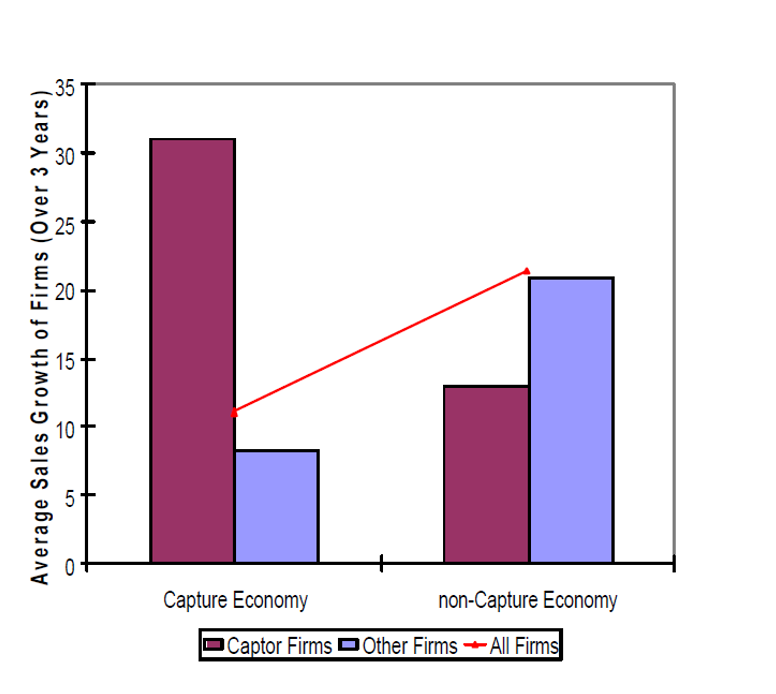

The notable exception to this trend relates to companies that operate in a market characterised by state capture who are able to become a ‘captor’ firm able to exercise undue influence over policymaking, regulation and enforcement (Batra, Kaufmann and Stone 2003). When an insider section of the business community is able to dictate the formulation or implementation of policies, laws and regulations, then any such ‘captor’ firms appear to benefit significantly from their insider status, with their sales growth being much higher than outsider firms. However, as shown in Figure 2 below, aggregate sales growth of all firms in markets characterised by state capture is markedly lower than in markets without state capture (Batra, Kaufmann and Stone 2003).

Figure 2: The Effect of State Capture on Enterprise Growth.

Source: Batra, Kaufmann, and Stone 2003.

Overall, the negative effects of corrupt practices on firm productivity and innovation suggest that corruption reduces the potential of private business activity to contribute towards inclusive growth and ultimately sustainable development.

Corruption and FDI

Numerous scholars have examined whether corruption stimulates or impedes inbound foreign direct investment. Studies on Europe (García-Gómez et al. 2024), Southern African countries (Chamisa 2020), Nigeria (Zangina and Hassan 2020) and Tunisia (Hamdi and Hakimi 2020) have concluded that improved control of corruption encourages inward foreign direct investment (FDI), although other research has found less conclusive evidence that a lower incidence of corruption is associated with higher FDI inflows in developing countries (Krifa-Schneider, Matei and Sattar 2022; Qureshi et al. 2021). A recent meta-review of the literature on corruption and FDI concluded that, while there is no unanimity, the majority of studies in the last two decades conclude that ‘corruption raises the cost of transactions, risks and uncertainties which inhibits FDI inflow’ (Zangina, Hassan and Harun 2020).

Indeed, many researchers have concluded that corruption is an important determinant of the size of FDI flows as well as their origin and destination countries. Cuervo-Cazurra (2006) argues that higher corruption in a destination country is associated with a lower overall size of inward FDI, but with a relatively higher proportion of inward FDI from origin countries that themselves have high levels of corruption. Mathur and Singh (2013) find that corruption acts as a brake on FDI, noting that less corrupt countries are more likely to provide investors with a conducive business climate, including reliable property protection, fewer capital constraints and lower non-tariff barriers. Indeed, in high-growth transition countries, Asiedu and Freeman (2009) identify corruption as the most important determinant of investment growth – ahead of firm size, ownership, trade orientation, industry, GDP growth, inflation and openness to trade. An empirical study of 48 countries from South and South-East Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa from 1998 to 2014 calculated that a 1% decrease in the level of corruption was associated with an increase of between 8% and 12% in FDI inflows (Hossain 2016).

In a cross-country empirical analysis of the impact of corruption on FDI flows, Belgibayeva and Plekhanov (2019)point to a virtuous cycle between investment flows and control of corruption. They find that there are greater investment flows between countries with good control of corruption, and that where corruption in the FDI destination country decreases, inward investment from countries with lower incidences of corruption increases more than from countries with high rates of corruption. As the quality of a county’s institutions and control of corruption improves, they suggest the destination country may attract less investment from countries with widespread corruption, while greater investment from less corrupt countries could further reinforce the strengthening of economic and political institutions that keep corruption in check.

Corruption and impact investing

Impact investments refer to ‘investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return’ (GIIN 2023). Impact investors can include fund managers, development finance institutions, pension funds, corporates and private foundations, and they chiefly use private debt and equity financial products to support investees (Transparency International UK 2022: 11). Capital provided by impact investors can make a significant contribution to closing the 2030 Agenda’s financing gap; the International Finance Corporation (2020) has estimated that 2020 levels of impact investing in private markets could equate to as much as US$2 trillion in assets under management.

Some of the most transformative impact investing takes place in emerging and frontier markets. These markets are often characterised by high rates of poverty, instability and corruption (Transparency International UK 2022: 2). Moreover, sectors commonly prioritised by impact investors – including infrastructure, renewable energy, finance and healthcare – present significant vulnerabilities to corruption (Transparency International UK 2022: 15). For instance, an investee company might pay bribes to procurement officials, regulators or inspectors to obtain a licence or contract, or to ‘evade accountability for environmental and social harms’ (Transparency International UK 2024: 2). The World Economic Forum notes that, where investments are plagued by corruption, this ‘distorts regulatory enforcement, [and] siphons money and attention away from public priorities’ (World Economic Forum 2022: 3).

Where impact investments are compromised by corruption, this can bring an array of financial, reputational, operational, security, legal and political risks for all parties, as well as likely negating the intended developmental impact of the investment (Transparency International UK 2024: 7). Investors interviewed by TI UK expressed concerns that corruption scandals can result in funding being suspended or withdrawn from investments (Transparency International UK 2024: 7).

Despite these concerns, observers note that most impact investors do not accord sufficient attention to the perils posed by corruption, and view business integrity largely as a compliance issue or a one-off due diligence exercise, rather than as an essential part of their development mandate and a priority commitment for investee entities (Lewis 2022). This may partly explain why corruption in private business and finance has been given limited attention in the financing for development agenda.

Anti-corruption measures for the business environment

Measures to curb corruption in the business environment can encompass both the demand and supply side.

On the demand side, a further distinction can be made between rule-making and rule-enforcement. At the level of rule enforcement, a whole range of preventive anti-corruption instruments to reduce administrative corruption could be considered helpful to reduce the risk of businesses colluding with or being extorted by dishonest officials. These include codes of conduct, robust human resource management, conflict of interest policies, whistleblower protection, proactive transparency, asset declarations, internal controls and audits. In addition, criminal law responses, such as criminalising and sanctioning foreign bribery and money laundering, have played a prominent role in efforts to reduce private sector corruption (Dell and McDevitt 2022; OECD 2021c; FATF 2010). Governments could also take steps to incentivise corporate anti-corruption compliance (OECD 2024a; Rahman 2020).

When it comes to rule making, efforts to disrupt undue influence over policymakers could help break the grip of special interest groups or captor firms on the economy and promote fairer competition. Relevant policy responses to promote political integrity could include restrictions on lobbying and the revolving door, as well as robust oversight over political finance regulations and beneficial ownership registers. The forthcoming OECD Principles on Responsible Corporate Lobbying and Political Engagement may serve as a useful reference point in future.

On the supply side, business integrity initiatives may help to establish a level playing field for private enterprise and overcome the collective action problem, whereby businesspeople feel compelled to engage in corruption to maintain or expand their market share. Businesses could seek to improve their ESG reporting through the use of consistent and transparent reporting frameworks. Numerous standards exist, including:

- the Business Principles for Countering Bribery

- the Business Principles for Countering Bribery: Small and Medium Enterprise (SME) edition

- the Equator Principles

- the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)

- the Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIIRS)

- the Global Reporting Initiative

- the International Integrated Reporting Council

- the ISO 37001 on Anti-Bribery Management Systems

- the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct

- the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises

- the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board

- the UN Global Compact Principles for Responsible Investment

In addition, there are a large number of business integrity platforms at both the global and national levels, such as the World Economic Forum’s Partnering against Corruption Initiative and the Global Initiative to Galvanise the Private Sector as Partners in Combatting Corruption. The Basel Institute on Governance has compiled a list of Collective Action Initiatives around the world.

Business integrity has been a theme of several resolutions passed at the recent UNCAC Conference of States Parties, one of which emphasised the importance of ethical business conduct among firms that contract with governments (United Nations 2023a: 4), while another encourages governments to strengthen incentives and reward companies that act ethically (United Nations 2023b).

Corruption’s effect on international development cooperation

The AAAA framework lists ‘international development cooperation’ as one of its key action areas to guide international efforts to align all development financing flows and policies with the economic, social and environmental priorities set out in the 2030 Agenda.

The AAAA states that official development assistance is an important complement to the efforts of poor and fragile countries to mobilise domestic public resources (United Nations 2015: 26). It also called for renewed focus on least developed countries and more coherence in humanitarian assistance when responding to emergencies such as conflicts and natural disasters (United Nations 2015: 27, 32). The AAAA emphasised the need for greater volumes and more effective use of both concessional and non-concessional financing from donors to improve essential public services and infrastructure, and it encouraged the use of new financial instruments such as blended finance where appropriate (United Nations 2015: 27).

Corruption’s impact on official development assistance (ODA)

A contentious issue in policy debates on foreign aid is the extent to which its effectiveness is affected by corruption, and especially how much development funding and humanitarian assistance is misappropriated by actors in aid-recipient countries (House Committee on Oversight and Accountability 2024).

The amount of foreign aid lost to corruption is inherently difficult to measure (Wathne and Stephenson 2021). One prominent paper recently established a positive correlation between aid disbursements to highly aid-dependent countries and bank deposits in offshore financial sectors with high levels of banking secrecy (Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers 2022). While not observing corruption directly, this study infers that development aid is associated with a ‘leakage rate’ of approximately 7.5% on average, which the authors attribute to capture by elites. This may constitute an underestimate as it only includes ‘aid diverted to foreign accounts and not money spent on real estate, luxury goods’ (Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers 2022: 4).

There are other assessments thatsuggest that, overall, the proportion of foreign aid lost to corruption may be smaller than the figure suggested by Andersen, Johannesen and Rijkers (2022). Kenny (2024), for instance, points out that, of the US$8.5 billion spent by the US on reconstruction projects in Afghanistan between 2012 and 2020, only 0.4% of audited costs were ultimately disallowed. Yet Kenny (2024) concedes this is probably an underestimate of underused funds as audits may fail to detect or overlook instances of corruption. Moreover, reports by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (2016) and the notorious Kabul Bank scandal illustrate how the extent and systematic nature of corruption in Afghanistan severely weakened the effectiveness of financing for development in the country (McLeod 2016).

The impact of corruption on ODA depends on a number of factors, including the ‘political economy context into which the aid is delivered [and] the way in which aid is delivered’ (Dávid-Barrett et al. 2020: 2).As such, it appears that some forms of development aid, notably humanitarian assistance, are especially vulnerable. According to Darden (2019), estimates by those working in the sector of losses to fraud and corrupt diversion of humanitarian assistance range from 2% to 15%. Between 2015 and 2019, for instance, the USAID Office of the Inspector General (2019) received 358 allegations of fraud, theft, misappropriation, bribery and other integrity breaches across its humanitarian operations in Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey and Syria.

Fraud and corruption in donor responses to emergencies is a particular problem. During the Ebola epidemic, documented corrupt practices included the widespread diversion of funds and medical supplies, misreporting of salaries and fraudulent payments for goods, petty bribery to bypass containment measures, such as roadblocks and quarantined zones, as well as flawed and opaque procurement processes (Dupuy and Divjak 2015). The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (2017) has estimated that it lost over US$6 million due to corruption and fraud during its Ebola outbreak operations from 2014 to 2016.

Moreover, while the scale of corruption in foreign aid may not be as extensive as claimed by some politicians in OECD DAC countries (Greenberg 2017), it is clear that corruption has a negative impact on the quality and quantity of international assistance delivered to populations in need. According to a survey conducted as part of the 2022 study The State of the Humanitarian System, only 36% of aid recipients agreed that aid reached those who needed it most (ALNAP 2022: 106). This suggests that affected populations perceive widespread corruption and mismanagement in the delivery of assistance and that the diversion or theft of resources supplied by aid agencies is a ‘top concern for communities’ (ALNAP 2022: 101). Not only can corruption reduce the amount of aid reaching the intended beneficiaries but poorly conceived humanitarian initiatives could potentially fuel further insecurity in crisis regions by providing incentives to armed actors to violently seize control of aid inflows (Keen 2008).

Revealingly, a study into delivering humanitarian aid to the most insecure environments by Haver and Carter (2016) identified corruption and the diversion of aid as one of the critical barriers to effectiveness, alongside staffing issues, finding suitable partnerships, negotiations with armed actors and communication with affected people.

Without adequate risk identification, mitigation and control measures, the spending of development funds can facilitate corrupt behaviour by donor staff, project beneficiaries or intermediaries (Adetunji 2013; Humanitarian Practice Network 1999; May 2016). Indeed, where donor agencies have weak integrity management structures, development projects can inadvertently exacerbate corruption in the very communities they seek to support (Hart 2016). It is important to note that multilateral organisations and development banks are not immune (Bergin 2023); Krys (2016) argues that corruption incidents at multilaterals are so common that they should not be treated as ‘isolated incidents’.

As such, a clear picture emerges of corruption’s damaging impact on the effectiveness of international development cooperation. As acknowledged by the OECD (2016b: 4), corrupt practices worsen development outcomes and reduce value for money in development assistance programmes. In addition, corruption scandals can undermine public support for official development assistance in donor countries (Dávid-Barrett et al. 2020: 2; Filipenco 2024). Populations in least developed countries are particularly vulnerable to situations in which corruption scandals lead donors to suspend their programming (Cliffe et al. 2023: 31).

Worse still, where aid becomes another source of rent for corrupt actors in aid-recipient countries, this can entrench their position and reduce their incentive to support economic or political reforms intended to foster inclusive and sustainable growth (Filipenco 2024). As such misappropriation of development assistance can spawn other governance challenges and beget further corruption. For instance, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (2016: 8) argues that foreign aid fuelled corruption in Afghanistan due to the ‘enormous influx of money relative to the size of the economy, weak oversight of contracting and procurement, and short timelines’.

Elite capture and aid diversion

The impartiality and needs-driven targeting of development assistance can be undermined by donor governments, host governments at the national and local levels, non-state armed groups and community gatekeepers, each of whom may attempt to influence aid allocation criteria and distribution patterns for self-interested or political reasons (Haver and Carter 2016: 26). In settings in which electoral politics are playing out, undue influence by local political functionaries can result in aid being directed to party cadres, supporters or vote banks (Khair 2017: 214-215).

The result is not only the diversion of funds intended for development projects in a way that reduces the overall impact of aid, but distorted priorities that neglect community needs and weaken local institutions’ capacity to effectively manage development initiatives.

A recent report into the humanitarian system called aid diversion a ‘fact of life’ in the sector (ALNAP 2022: 118). In a survey for that report, 73% of aid workers who answered stated that corruption was a moderate or high concern in the country they were operating in, while 22% of aid recipients identified aid diversion as the primary problem they faced, which was second only to insufficient quantities of aid (34%) (ALNAP 2022: 118).

Procurement practices

A large proportion of development aid is disbursed through public procurement systems in aid-recipient countries, which can be highly vulnerable to corruption (Collier, Kirchberger and Söderbom 2016). Yet there are also potential integrity risks related to donors’ own procurement processes, not least given that a large proportion of bilateral donor assistance is contracted to companies from the donor country, which may heighten the potential for a conflict of interest with suppliers (Kenny 2024).

In the least developed countries and crisis-affected regions, aid agencies often face constraints on their ability to oversee or audit this spending. As such, standard integrity risks in procurement may be heightened, including manipulated tender specifications, collusion in the bidding process, bribery in the tender evaluation, embezzlement during contract implementation, falsification of receipts and other fraudulent practices, and poor record-keeping (Shipley 2022: 6; Maxwell et al. 2008: 15).

For example, a US based NGO was forced to pay around US$5 million to settle allegations that it had violated procurement regulations when supplying humanitarian aid to Afghanistan and Pakistan and had failed to adequately monitor its sub-contractors who were engaged in corrupt practices (US Department of Justice 2014).

Service delivery

Corruption can also occur at the point of delivery of public services funded by aid. In South Sudan, for instance, government authorities and armed opposition groups ‘routinely seek to influence the location of [aid] distribution’ (Haver and Carter 2016: 55). In the DRC and Yemen, ALNAP (2022: 119) found that various intermediaries had intercepted cash and charged recipients for assistance. Similarly in Somalia and Yemen, community power holders have been shown to interrupt the distribution process to prevent it disrupting existing patronage networks (Haver and Carter 2016: 12). These corrupt abuses of power can mean that money does not reach the most vulnerable populations or fund public services critical to poverty reduction, such as health and education.

Sexual corruption

Development assistance is often delivered in an environment characterised by widespread sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) (Donli 2020). Sexual abuse by armed groups and peacekeeping forces is well documented (Alexander and Stoddard 2021), but in recent years aid workers themselves have come under scrutiny (Flummerfelt and Peyton 2020). A report by the House of Commons (2017: 11, 19) concluded that such abuse is ‘endemic’, and noted that in Syria, sexual abuse and exploitation by aid workers at aid distribution points is an ‘entrenched feature’ of the lives of women and girls. Meanwhile, reporting by Kleinfeld and Dodds (2020) on the DRC indicates that accountability for SEA by aid workers can be rare as aid agencies’ reporting mechanisms are often ineffective and perpetrators pay off victims.

Despite these clear risk factors, aid agencies have historically been slow to respond to non-financial forms of corruption in humanitarian responses (Maxwell et al. 2008: 12). A particular risk is known as sexual corruption or (sextortion), which occurs when ‘those entrusted with power use it to sexually exploit those dependent on that power’ (Feigenblatt 2020). In the context of development aid, this often manifests as perpetrators with access to resources like food, medicines or shelter withholding such resources from people in need in order to coerce sexual acts from them. According to interviews conducted by IRC with internally displaced persons in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, 60% of people questioned knew of women and girls who had to exchange sex for food or petty cash (International Rescue Committee 2021).

Corruption and blended finance

Blended finance – the mixture of development funds with commercial finance to fund investments in low and middle-income countries – has been hailed as a means of filling the finance gap between actual public spending and the resources required to pay for sustainable development. Yet even advocates of blended finance note the ‘inherent risk’ of conflict of interest involved when mixing the logics of profitability and development (Pegon 2019; Helms 2018).

Integrity risks can arise from a misalignment between mandates, incentives and accountability systems between entities involved in blending. First, the participation of profit-driven actors such as impact investors, commercial banks and administrators of pension or sovereign wealth funds who may be unfamiliar with development assistance entails potentially novel integrity risks, such as conflicts of interest or inadequate due diligence procedures. Second, the complex financing arrangements, numerous intermediaries and multi-layered governance structures involved in blended finance projects may exacerbate potential integrity risks. This is because the involvement of multiple entities can make managing transactions and monitoring results difficult, which in turn can lead to opacity and a diffusion of responsibility that increases fiduciary risk and makes it less likely that corruption would be detected.

There are other operational level factors in blended finance operations that can lead to integrity breaches, including corruption, fraud, money laundering, tax evasion and undue influence (International Finance Corporation 2017: 2). Foremost among these is a lack of transparency at both portfolio and project levels (Jenkins 2022). Blended finance projects are considerably less transparent than projects funded using other forms of official development assistance (International Trade Union Confederation 2018: 45). Data related to how financial intermediaries invest funds (sub-investments) is virtually non-existent (Tri Hita Karana Transparency Working Group 2020: 21; Publish What You Fund 2021: 48). The Tri Hita Karana Transparency Working Group (2020: 21) also points to a ‘blanket refusal’ on the part of entities involved in blended finance transactions to disclose details about their beneficial owner.

Other risk factors include the routing of blended finance transactions through offshore financial centres, the lack of necessary market expertise on the part of donors, a dearth of participatory opportunities for affected communities and aid-recipient governments, as well as political exposure (Jenkins 2022).

Anti-corruption measures for development cooperation

Given the sheer diversity of uses of official development assistance, tackling corruption’s impact on the quantity and quality of aid requires a wide range of policy instruments. These will need to be tailored to the specific conditions of a development intervention, such as specific sector, aid modality, geography and local political economy. Common themes nonetheless include the aid transparency initiatives, the establishment of robust corruption risk management systems, strong internal controls over organisational resources, ensuring a high degree of downward accountability, and earmarking a proportion of total aid for good governance programming and civil society oversight.

Aid transparency

Where development agencies publish accurate and timely information about their financial support, this can allow intended beneficiaries, journalists, CSOs and oversight bodies to identify whether the aid reaches its target and report suspicious cases to donors. As well as reducing opportunities for corruption, aid transparency often facilitates coordination with other actors, including partner government bodies, other donors and NGOs on the ground, which in turn can minimise the risk of duplication and fraud (Glennie et al. 2021: 2).

In addition to financial data, donors should also publish their activity plans and clearly link their spending commitments to stated desired outcomes. As the UNODC (2020) points out, the use of clear, objective and transparent criteria to identify intended beneficiaries is crucial to reduce the risk of corruption that can arise where those responsible for delivering aid enjoy a high level of discretion in selecting recipients. Development agencies should ensure that those eligible for assistance are made aware of the nature and level of support they are entitled to and the method by which this will be delivered.

Specifically on blended finance, Collacott (2016) argues that information on the activities of investors and financial intermediaries needs to be made available to ensure that ODA being used in blending complies with agreed standards of untied aidda5ce0fee472 and that it is not generating distortions in local markets. The OECD (2018: 123) emphasises that ‘transparency regarding blended finance opportunities is decisive in establishing fair competition’ and that a lack of transparency can undermine the impact of blending on development outcomes and market growth.

Donors and multilateral banks could make use of existing initiatives such as the International Aid Transparency Initiative. Publish What You Fund is another initiative that has developed aid transparency principles for bodies engaged in funding and delivering aid as well as for those who deliver aid on their behalf.

Corruption risk management

Various standards for corruption risk management in development cooperation have been issued, including by the OECD. Typically, these stipulate that international development agencies should establish a comprehensive corruption risk management system that includes codes of ethics, integrity advisory services, training, whistleblowing mechanisms, robust audit functions, risk assessment tools, political economy analysis, tough sanctions, coordination channels to respond to corruption cases and communication protocols in the event that corruption is detected (U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre 2021; Nicaise 2023; Johnsøn 2015). Due diligence of potential partners’ corporate structures, business models and transparency standards is particularly important to identify any politically exposed persons, criminal activities, civil proceedings or political influence. The GOVNET Anti-Corruption Task Team is one initiative that seeks to help donors and aid-recipient countries to curb corruption in development cooperation.

Downward accountability

Anti-corruption and fraud prevention measures can help aid agencies to account to donors for the money spent. Yet this type of upwards accountability should not come at the expense of downward accountability to affected communities (Haver and Carter 2016: 50). Aid agencies are increasingly expected to adhere to the Accountability to Affected People (AAP) framework. This calls for development actors to take account of, give account to and be held to account by people affected by a crisis. The AAP framework stresses the importance of sharing timely and actionable information with communities, supporting the meaningful participation and leadership of all affected people and ensuring feedback systems are in place to enable communities to assess and comment on the performance of humanitarian action, including corruption. At the project level, better consultations with affected communities could help increase oversight and reduce integrity risks such as fraud, bribery and embezzlement (Komujuni and Mullard 2020).

Earmarking

Finally, there are calls by some commentators for a certain proportion of official development assistance to be earmarked for good governance programming (Evans 2022; Rahman 2022), or for a small percentage of aid budgets to be allocated for civil society oversight (Partnership for Transparency 2024: 13-14).

Corruption’s effect on international trade

The AAAA framework lists ‘international trade’ as one of its key action areas to guide international efforts to align all development financing flows and policies with the economic, social and environmental priorities set out in the 2030 Agenda.

The AAAA states that international trade operates as an ‘engine for inclusive economic growth and poverty reduction’ (United Nations 2015: 37). It calls for the consolidation of a ‘rules-based, open, transparent, predictable, inclusive, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system’, as well as trade liberalisation and measures to reduce protectionism (United Nations 2015: 39). Another stated ambition is the promotion of exports from least developed countries as a means of increasing productive employment and decent work in low and middle-income countries (United Nations 2015: 38). Finally, the AAAA points to the need to clamp down on illegal logging, mining, fishing and the illegal wildlife trade(United Nations 2015: 42).

Corruption and international trade

Much of the research on corruption and international trade has focused on whether trade openness is correlated with lower rates of corruption, and the direction of causality (Ades and Di Tella 1999; Treisman 2007; Park 2003; Gurgur and Shah 2002; Sequeira 2013; Badinger and Nindl 2014). Less academic attention has been paid to how corruption impacts the potential developmental effect of international trade.

Nonetheless, there is clear evidence that corruption has a deleterious effect on the potential of international trade to act as an ‘engine of development’ in several respects. First, administrative corruption in the customs sector reduces tax revenue due to the state from international trade. Second, the weight of evidence suggests that, at the aggregate level, corruption acts as a brake on the volume of international trade. Third, forms of political corruption, especially state capture, are associated with protectionist policies and lower exports. Finally, corruption can also play an enabling role in illicit trade.

Corruption’s impact on customs revenue

Corruption affects the work of customs administrations by obstructing the collection of import and export duties and tariffs and hindering the ability of customs agencies to control the entry and exit of harmful goods (Imam and Jacobs 2014).

Corruption in customs is typically either collusive or coercive. In collusive arrangements, importers/exporters bribe officials to evade duties or goods inspections. Coercive corruption can involve customs officials extorting traders by, for example, threatening them with spurious fees or tariffs (Ardigó 2014). Other risks include fraud embezzlement perpetrated by customs officers. In addition, trade misinvoicing can be linked to efforts to launder the proceeds of corruption (Global Financial Integrity 2014).

In total, corruption within customs authorities is thought to seriously undermine a state’s revenue collecting capacity. While estimates of global customs revenues lost to corruption are inevitably very difficult to calculate, one estimate puts the cost of corruption in customs at around US$2 billion per year (Michael 2012). Sequeira and Djankov (2014) find that collusive corruption results in the reduction of the average nominal tariff rate of around 5%. A more recent paper calculated that, in Madagascar, corruption in customs results in tax revenue losses of around 3% of total taxes collected (Chalendard et al. 2023).

Corruption’s impact on the volume and pattern of international trade

Thede and Gustafson (2012) have observed that the level, prevalence, location, function and predictability of corruption are important determinants of the volume and pattern of international trade.

In general, it appears that higher rates of corruption correspond to lower volumes of international trade. The World Bank (2014) found that 15% of firms worldwide expect to have to pay a bribe to get an import licence, which acts as a severe deterrent to market entry. Even where foreign companies are able to gain a foothold in a corrupt market, studies have shown that greater levels of corruption are associated with higher firm exit rates, suggesting that corrupt environments are highly unstable for businesses (Hallward-Driemeier 2009).

Doubtless, some individual, well-connected firms importing or exporting goods benefit from collusive forms of corruption to secure favourable arrangements from unscrupulous officials. Nonetheless, there is now widespread academic consensus that this behaviour comes at the expense of other firms and that the aggregate effect of corruption at the border is to constrain international trade flows (Ali and Mdhillat 2015; Zurawicki and Habib 2010; Dutt and Traca 2010; De Jong and Udo 2006; Musila and Sigué 2010; Thede and Gustafson 2012).

Administrative corruption – particularly coercive corruption – is thought to be especially damaging to trading firms because it imposes additional transaction costs on trade, functions as a hidden tariff and generates inefficiencies (Lejárraga 2013).

Exporters and importers rely on customs agencies to approve the transit of goods quickly and without extra costs to maintain profitability and competitiveness. Yet demands for bribes can cause delays; Freund, Hallward-Driemeier and Rijkers (2016) estimate that extortion by customs agents increases the time taken to clear customs by 1.2 times when exporting. Such delays are likely to reduce the competitiveness of exporting firms in international markets (Shepherd 2013; Hayakawa, Laksanapanyakul, and Yoshimi 2019).

Second, illicit payments to officials are essentially additional expenses that ultimately raise production costs, with knock-on effects on the price of exporting goods, again resulting in reduced competitiveness (Duvanova 2014). Firm-level data on informal payments from the 2010 World Bank Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey found that in some European countries, bribery imposed an additional tax on businesses representing as much as 10% of their sales (World Bank 2014). These bribes paid to customs agents represent an opportunity cost that firms could have more productively invested.

Kumanayake (2024) finds that corruption in customs agencies serves as a strong deterrent to domestic firms wanting to export goods abroad. His analysis of a business survey of nearly 6,000 firms across European and Central Asian countries finds that those companies who report to have been asked by customs officials to pay a bribe have a share of direct exports that is 52.7% lower than those firms who did not encounter coercive corruption in customs. This illustrates how high levels of corruption in customs lead to exporting firms engaging third parties to navigate customs processes, which is an additional cost that may reduce their overall competitiveness (Kumanayake 2024). Another study on Tunisian SMEs also points to corruption’s negative effects on the performance of export-oriented companies, finding that corruption in a firm’s home country reduces export intensity (Bahri, Sakka and Kallal 2021).

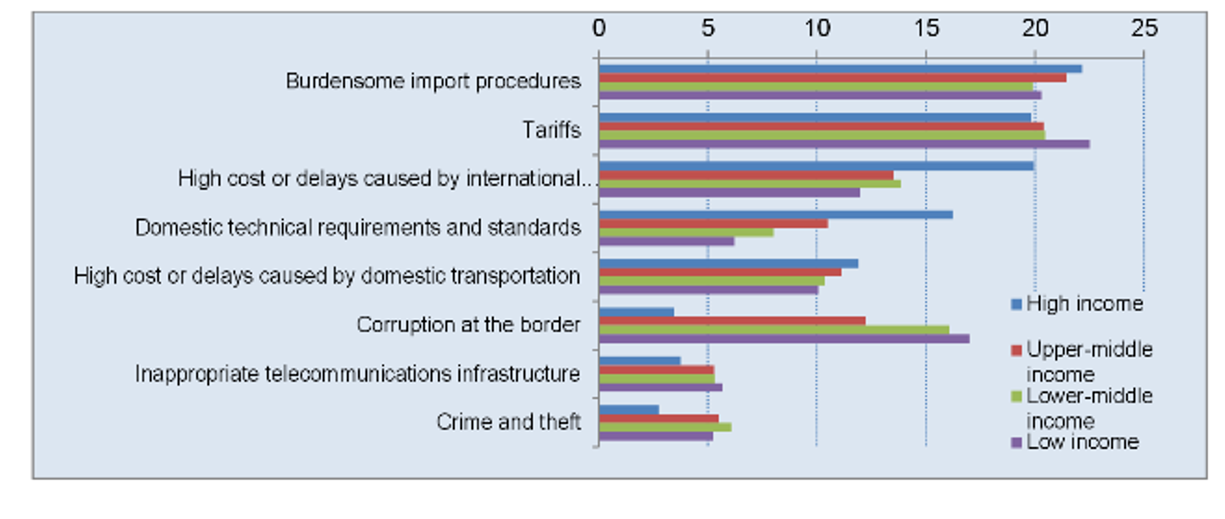

Only in very high tariff environments is the marginal effect of corruption found to be trade-enhancing; in around 90% of cases studied by Dutt and Traca (2010), corruption acted as a barrier to trade. This finding appears to hold across income classifications. Bahoo, Alon and Floreani (2022) establish that OECD countries trade less with countries with a high incidence of corruption. Data collected by the OECD and WTO (2015) indicates that corruption at the border is even more problematic for importing and exporting firms in lower-middle and low-income countries.

Figure 3: The most problematic factors for importing and exporting

Source: OECD and WTO (2015).

Lejárraga (2013) observes that where tariffs are hidden or unpredictable, companies cannot account for them in investment decisions or profitability calculations, and such uncertainty is a powerful deterrent to trade. In this vein, De Jong and Udo (2006) concluded that, while corruption is generally detrimental to international trade, uncertainty about the value of the bribe that firms have to pay customs officials has a particularly damaging effect on their willingness to export or import goods. Other studies concur, finding that firms in Southern African countries are willing to incur much higher transport costs to travel to more distant ports to avoid the ‘uncertainty associated with the level of coercive bribe payments at the most corrupt port’ (Sequeira and Djankov 2014).

Corruption’s impact on trade policy

Studies show strong associations between corruption, protectionist regimes and opaque bureaucratic systems (Bjørnskov 2012; Bandyopadhyay and Roy 2007). Dutt (2009), for instance, finds that ‘corruption is significantly higher in countries with protectionist trade policies’. There are two main channels through which corruption can exert a long-term negative impact on trade openness.

On the demand side, politicians and public officials looking to extract bribe payments have incentives to create more regulations, restrictions and administrative procedures to generate more opportunities to extort payments from citizens and companies. Wallis (2006: 25) argues that, in systemically corruption polities, ‘politicians deliberately create rents by limiting entry into valuable economic activities, through grants of monopoly, restrictive corporate charters, tariffs, quotas, regulations’ in order to enrich certain interest groups and shore up their political power. This has a detrimental impact on the regulatory environment and the efficiency of the state apparatus, and unnecessary red tape can breed inefficiencies as the practice of obstructing matters until facilitating payments have been made spreads across the public service (Argandoña 2005; Dzhumashev 2008).

On the supply side, Mungiu-Pippidi et al. (2018: 14) contend that, in highly corrupt settings, domestic rentier companies often attempt to influence the regulatory framework to maintain or expand their market domination. As their business model relies on corrupt or at least cosy relations with government officials, these firms may resist trade liberalisation measures to prevent the entry of new competitive companies into the market. Special interest groups may, for instance, seek to exercise undue influence over trade negotiations to create exceptions and preserve their privileged position (Alemanno and Karttunen 2016). Interestingly, Faruq, Webb and Yi (2013) argue that ‘it is typically the less productive firms facing stiff competition who are most likely to turn to corruption to expand or maintain market share’.

The influence of corruption over trade policy can result in domestic firms in a captured economy becoming less competitive, which in turn may inhibit export-led growth. In Pakistan, for instance, Malik and Duncan (2022: 41) find that the

‘capture of trade policy by politically powerful groups has profound consequences for Pakistan’s development […] The import protection afforded to such interest groups entrenches the anti-export bias of Pakistan’s trade policy, which is considered as a major drag on Pakistan’ development. There is an inherent relationship between higher import protection, stagnating exports, and current account imbalances.’

They also suggest that capture of trade policy by special interest groups in some developing countries has led to liberalisation actually resulting in greater trade protection and higher rents than before liberalisation (Malik and Duncan 2022: 41).289ad8bdf7a6

Corruption and illegal trade

At every stage of the process, corruption plays an important role in facilitating illegal trades in timber, fish, wildlife and other natural resources, as well as narcotics, tobacco products, counterfeit goods and human trafficking (EUROPOL 2023; OECD 2021a; FATF 2012). In the wildlife trade, for instance, Zain (2020), Wyatt (2017) and Martini (2013) show how corruption underpins

‘many of the crimes along the wildlife trade route, from poaching (e.g. illegal payments to issue hunting licenses, bribery of forest patrol officers), to trafficking (e.g. bribery of customs officials, illegal payments to issue export certificates, etc), to law enforcement (e.g. bribery of police officers and prosecutors to avoid investigations; illegal payments to manipulate court decisions).’

Likewise, in the fisheries sector, ‘corruption provides a way for fishers to sustain illegalities and avoid penalties and imprisonment, and, in turn, illegalities provide opportunities for many stakeholders to gain financially’ (Nunan et al. 2018: 74). Similar observations have been made in the forestry and mining sectors (Miller 2011; Smith et al. 2012; Cerutti et al. 2013; Teye 2013; Sundström 2016; Knutsen et al. 2017; Dong, Zhang, and Song 2019; Zabyelina and van Uhm 2020; Crawford and Botchwey 2017).

According to the OECD (2016a), corruption is a key driver of the ‘illegal and unsustainable mineral extraction, forestry, fishing, [and] trade in wildlife’. Not only does a large proportion of total illegal trade stem from the illicit exploitation of environmental resources but these are often associated with ‘the unsustainable use of finite natural resources’ (Slany, Cherel-Robson and Picard 2020: 10) which have ‘severe environmental impacts’ (UNCTAD 2020: 143-144).

Environmental crime is thought to generate anywhere between US$110 billion to US$281 billion per year (Slany, Cherel-Robson and Picard 2020: 10). The profits from these criminal activities create opportunities for corruption and money laundering and have wider destabilising effects. For example, the illicit mining of minerals and fuel smuggling stimulate conflict, fund armed groups and lead to human rights abuses (UNCTAD 2020: 142). Shaw, Nellemann and Stock (2018) estimate that 38% of all illicit flows to non-state armed groups in conflict originate in the illicit extraction of natural resources.

A recent study by EUROPOL (2023: 19) reveals how corruption among border officials serves as the ‘key enabler of the criminal infiltration of ports’ in Europe, which underpins drug smuggling and human trafficking networks in the region.

Anti-corruption measures for international trade

Many of the potential policy instruments to curb corruption in international trade are similar to those discussed in the section on corruption in the business environment.

In addition, however, international trade negotiations offer a potential entry point for anti-corruption. Despite being built on the underlying principles of transparency and non-discrimination, the global trade system overseen by the WTO regime has limited purview over so-called ‘deep provisions’ in trade agreements, such as governance issues (Jenkins 2018a). In the absence of measures at the WTO level to improve transparency and reduce bribery in international trade, some countries including the US have taken steps to embed anti-corruption and transparency provisions into their bilateral trade agreements.

There is now some consensus around best practice anti-corruption and transparency provisions for inclusion in trade deals, such as explicit references to international anti-corruption conventions, commitments to criminalise active and passive bribery, non-criminal sanctions for firms where they are not subject to criminal liability, and whistleblower protection (Jenkins 2018a). By providing an economic incentive, trade agreements that require their signatories to ratify anti-corruption conventions or enact de jure anti-bribery measures can encourage and accelerate the diffusion of good governance and transparency norms in international trade (Lejárraga and Shepherd 2013).

Where transparency and anti-corruption provisions are embedded into trade agreements, this can reduce opportunities for discretionary behaviour such as rent-seeking and arbitrary decision-making, allowing firms to compete in foreign markets with greater confidence that they will receive fair treatment from public officials and agencies (Lejárraga 2014). Improving the transparency of the trading environment is thus an important complement to traditional means of reducing barriers to trade, such as lowering tariffs.

Trade agreements with extensive transparency mechanisms are found to have a greater positive effect on trade flows than those with shallow commitments to transparency (Lejárraga and Shepherd 2013). A study of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) countries, for instance, found that improving trade-related transparency could raise inter-APEC trade by approximately US$148 billion or 7.5% of baseline trade in the region (Helble, Shepherd and Wilson 2009).

Given the risk that certain entities exercise undue influence over international trade negotiations, compliance with global standards such as the OECD (2024b)Recommendation on Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying and Influence could reduce opportunities for special interest groups to dominate proceedings.

Finally, addressing the role of corruption as a facilitator of illicit trades in timber, fish, wildlife, narcotics, counterfeit goods and humans will require law enforcement approaches with a focus on organised criminal groups. Some commentators have called for better coordination between initiatives related to the United Nation’s Convention against Corruption and those under the UN Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (Transparency International and Global Initiative on Transnational Organized Crime 2021; Tennant 2021; UNODC 2023). Other initiatives relevant to efforts to curb corruption in international trade include the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime, the World Custom’s Organisation’s Integrity Sub-Committee, the Fisheries Transparency Initiative and the Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade.

Corruption’s effect on debt sustainability

The AAAA framework lists ‘debt sustainability’ as one of its key action areas to guide international efforts to align all development financing flows and policies with the economic, social and environmental priorities set out in the 2030 Agenda.

The AAAA states that sovereign borrowing is ‘an important tool for financing investment critical to achieving sustainable development’ (United Nations 2015: 43).However, debt sustainability is a major challenge, as nearly 40% of developing countries suffer from severe debt problems (United Nations 2015: 43). Currently, 3.3 billion people live in countries whose governments spend more on servicing debt than on health or education (United Nations 2023c: 14). The AAAA called for the establishment of a central data registry on debt restructurings and improved transparency in debt management (United Nations 2015: 44).

Corruption’s impact on debt sustainability

Some research points to the role that corruption can play in triggering sovereign debt crises, alongside other variables such as poor macroeconomic policies and external shocks. Studies by Cooray, Dzhumashev and Schneider (2017) and Apergis and Apergis (2019) have found that corruption is associated with an increase in public debt, an effect that Del Monte and Pennacchio (2020) observe to be independent of the size of government expenditure. Interestingly, Kim, Ha and Kim (2017) find that in highly corrupt countries, public debt constrains economic growth, while in countries that do well in controlling corruption, public debt can enhance economic growth.

It is possible that corruption contributes to unsustainable debt accumulation as corrupt officials prioritise short-term private interests over the longer-term public interest. For example, unscrupulous politicians might take on debt to finance ‘white elephant’ projects that provide little development impact but offer ample opportunities to siphon off funds or award lucrative contracts to politically connected firms (National Democratic Institute and Transparency International 2024: 3).

Alternatively, incumbent administrations may take on unsustainable additional debt ahead of elections to reward their patronage networks and shore up their political support in an attempt maintain power. A recent study observed that primary deficits in developing countries rise on average by around 0.6% percentage points of GDP during elections, which the authors note over time can threaten the sustainability of public finances (de Haan, Ohnsorge and Yu 2023). Such lending patterns have also been observed at the local level during electoral cycles (Bircan and Saka 2021).

The opacity of many debt financing arrangements may also create further vulnerabilities to corruption. As acknowledged in the AAAA, the opacity of many debt arrangements is a serious challenge to sound governance and public financial management, and several national crises in recent years demonstrate that this lack of transparency can have macroeconomic implications. The National Democratic Institute (2022: 1) has defined opaque debt as ‘non-transparent lending and borrowing that is done in such a way that the funds are unable to be tracked and neither governments nor lenders can be held accountable for their financial decisions’.

Opacity is a feature among both borrowers and creditors. According to the World Bank, between 2019 and 2021, over 40% of low-income countries did not publish any data on their sovereign debt (Rivetti 2021: 1). An IMF report likewise finds that fewer than 50% of the 60 countries they analysed have debt disclosure or reporting requirements in their domestic legal frameworks (Vasquez et al. 2024). Certain creditors, including China, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates reportedly provide especially opaque loans that can feature confidentiality clauses stipulating that the terms cannot be disclosed to other creditors or the public (National Democratic Institute 2022: 1). Similarly, many of the loans by private creditors are not disclosed; one advocacy group claimed to have found US$37 billion in undisclosed loans from 19 private banks (Financial Times 2024). As such, much of this lending is not included in official global debt statistics or assessments by private credit rating agencies (Malik and Parks 2021).

Such opacity on the part of government officials taking on new public debt can provide opportunities for corrupt behaviour. Without controls to scrutinise debt negotiations, their conditions and the management of debt-related funds, resources are more vulnerable to being embezzled, misappropriated or lost due to other corrupt practices across the budget cycle.

In some cases, this misuse of public finance to advance narrow financial or political interests can result in governments being compelled to curtail social spending to cover debt repayments. Moreover, as the examples below demonstrate, hidden debt scandals can erode creditor confidence in a country’s financial management, driving up the cost of borrowing and undermining debt sustainability (National Democratic Institute 2022; Christel 2024). Overall, the UN Inter-Agency Task Force on Financing for Development (2023: 19) concludes that the extent of corruption is an important factor in a country’s capacity to carry debt.

The cases of Mozambique and Sri Lanka illustrate how weak oversight over public finances can reduce constraints on officials taking on opaque debt, and how this in turn renders funds vulnerable to corruption and fiscal mismanagement that further weaken governance capacity (National Democratic Institute 2022: 9).

In collaboration with employees in an international bank, a group of senior Mozambican government officials secured US$2.2 billion in off-budget loans that were not publicly disclosed. Ostensibly intended to build a fishing fleet and fund maritime security, large amounts of these funds were instead diverted to private pockets.3068fbd85391 The discovery of the scandal contributed to an economic downturn in 2016 and has set back efforts to reduce persistent poverty and inequality (Shipley 2019).

After taking on opaque debt and being unable to repay its Chinese creditors, Sri Lanka signed over a strategic port to China in 2017 (National Democratic Institute 2022: 2). In 2022, the country declared bankruptcy and defaulted on its debt, causing severe hardships on its populace. Encouragingly, during the US$2.9 billion IMF debt-restructuring process, a civil society coalition carried out a shadow governance diagnostic assessment of the country’s anti-corruption landscape, to which the IMF referred when including anti-corruption safeguards into the loan package (National Democratic Institute and Transparency International 2024: 6).

It is important to note the complicity of creditors in these arrangements. As Vogl (2024) writes,

‘private sector lenders, notably banks issuing sovereign bonds, have at times engaged in outright fraud – as Credit Suisse did in a $2 billion bond deal for Mozambique; as did Goldman Sachs in a $6 billion bond deal for Malaysia. All too often, the rating agencies have ignored corruption when assessing risks associated with sovereign bond issues. Banks underwriting the bonds have similarly ignored corruption and focused solely on the yield that can be secured.’

Anti-corruption measures for debt sustainability

Commentators have identified several channels to reduce the risk that opaque debt is used in a corrupt manner: more transparency, better oversight of sovereign debt, stronger public financial management systems and civil society participation.

First, the United Nations Economic and Social Council (2024) recently acknowledged that transparency ‘enables more effective debt management by debtors and better risk management by creditors […] transparency also enhances accountability by allowing the public to monitor how public debt is managed’. As such, greater transparency can help ensure that ‘lending does not fuel corruption and that decisions are made to benefit the larger public’ (National Democratic Institute and Transparency International 2024: 3).

Multilateral and bilateral lenders could strengthen the requirements for public disclosure of institutional and instrumental debt and improve cooperation in sharing debt-related information, including through a centralised public database (National Democratic Institute and Transparency International 2024). Some observers have called for the United Kingdom and New York state, whose laws govern international debt contracts, to introduce a requirement for public disclosure of any loans to governments (Byrne and Rivera 2024).

For their part, borrowing countries could choose to proactively disclose all loans clearly distinguishing between the types of institutions and their various instruments (conditionalities and liabilities). Borrowing states could enhance the capacity of debt management offices, including by improving processes to gather, disclose and monitor debt-related information, potentially with the support of donors (IMF 2023). Another option could be to better regulate transparency provisions in public debt such as limiting the level of discretion that officials have to classify debt contracts as confidential on the grounds of national security.

Ultimately, as Rivetti (2021: 2) states, steps to improve transparency could lead to better quality investments and lower rates of corruption.

Second, measures could be taken to enable oversight actors such as parliaments, supreme audit institutions and civil society organisations to monitor debt (National Democratic Institute and Transparency International 2024: 3). This could involve formal procedures for parliaments, debt management offices and supreme audit institutions to approve and monitor debt.

Third, broader reforms to strengthen public financial management systems could help reduce any abuse of sovereign debt and ensure the funds are used as intended. Robust controls over resource allocation, public procurement, expenditure and oversight are important in this regard, particularly when it comes to extrabudgetary provisions.

Fourth, meaningful consultations with civil society during debt negotiations and restructuring processes could help uphold the public interest, while CSOs may also be in a position to contribute to governance diagnoses, as in Sri Lanka (National Democratic Institute and Transparency International 2024: 6).

Several existing initiatives promote good practices in debt transparency and accountability. These include the IMF and World Bank’s Multipronged Approach to Address Debt Vulnerabilities, G20 Operational Guidelines for Sustainable Lending, USAID Debt Transparency Monitor, the World Bank’s Debt Reporting Heat Map and the OECD Debt Transparency Initiative focused on private sector lending. The National Democratic Institute and Transparency International (2024) also recently published a checklist to support accountability actors, civil society organisations, to improving debt transparency and accountability.

- As of May 2022, the top 10 biggest US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act cases of all time, in terms of financial penalties and disgorgement, ranged between US$700 million and US$3.3 billion (World Economic Forum 2022: 5).

- When deployed by bilateral donors, blended finance can exhibit some of the characteristics of tied aid, where lucrative development contracts are restricted to commercial entities from the donor country. Bilateral development finance institutions draw much of their funding from their national governments, which often seek to further their own country’s interests when providing development financing. Evidence gathered by the OECD (2024c) indicates that tied aid increases the costs of a development project by between 15% and 30%. The OECD (2021b: 9) concedes that ‘risks regarding tied aid could potentially be higher in cases of blended finance’, and recommends that donors ‘should strive to remove the legal and regulatory barriers to open competition for aid- funded procurement’.

- They explain that politically connected actors in some sectors have been able to secure protectionist non-tariff measures, even as tariffs have been reduced (Malik and Duncan 2022: 41).

- An independent audit commissioned by the Office of the Public Prosecutor in 2017, found inconsistencies of at least US$500 million regarding how the loan proceeds were actually used. An indictment filed by the US Department of Justice in New York in late 2018 alleged that at least eight individuals received bribes and kickbacks of over US$200 million from the maritime projects (Shipley 2019).