Query

Please provide an overview of the impact of ESG on anti-corruption behaviour in companies and how anti-corruption is considered in the EU and US.

Caveat

It is important to note that the ESG reporting is dynamic with evolving regulations. This paper mainly focuses on ESG disclosure. In terms of reporting frameworks, this paper focuses on mandatory reporting requirements in the European Union and United States. For an overview of anti-corruption in voluntary ESG standards please refer to the paper here.

Understanding ESG

The environmental, social and governance (ESG) concept was first mentioned in a 2004 report from the United Nations – titled Who Cares Wins (UN Global Compact 2004; Byrne 2022a; Byrne 2022b). The report delineated that more sustainable markets and higher long-term financial returns might be achieved by taking ESG concerns into account in investing decisions. Over the last few decades, growing out of the need for responsible and sustainable business practices, ESG criteria are now being applied to corporate reporting, investing and strategies.

The heightened recognition of ESG considerations is evident across various stakeholders, including investors, consumers and regulators (Frey et al. 2023). With investors’ increasing emphasis on evaluating companies not just on their financial profitability but also on their performance with regard to ESG aspects, the phenomenon is predicted to evolve and expand. For instance, a report from KPMG (2022: 6, 14) predicts that with customers focused on justice and equality, and as the expectations of business stakeholders progress, organisations “will likely have no choice but to embrace ESG”.

Simultaneously, globally, the regulatory landscape is rapidly evolving, with various jurisdictions mandating ESG disclosures and new regulations and standards coming into place (Cifrino 2023). As a result, companies are under pressure to address their approach to ESG to meet regulatory demands and avoid reputational harm due to non-compliance (KPMG 2023). Thus, incentives from the market and tightening frameworks of disclosure are promoting greater action in the ESG sphere.

Simply put, ESG criteria are used to evaluate a company's actions in three primary areas: their environmental record, their level of social engagement and the governance practices that they employ. Although primarily used in capital markets, ESG ratings and the data derived from them offer valuable insights for investors and executives regarding a company's historical performance and impact at large. This information also plays a significant role in determining a company's risk exposure and potential future financial performance (Sustainalytics 2022a: 4).

Ensuing reporting in this area is referred to as ESG disclosure. While such disclosure requirements are mandated by certain stock exchanges, regulatory bodies and other government entities, there also exist a plethora of voluntary frameworks for ESG reporting, for example, Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), among others (Peterdy 2023).

ESG is also considered in investing, which involves evaluating long-term environmental, social and governance challenges and developments while considering positive actions that contribute to environmental protection, responsible business conduct and good corporate governance practices. The degree to which ESG investment incorporates social impact, potentially affecting financial risks or reducing expected returns, may align it more closely with social impact funds (Boffo and Patalano 2020: 14).

However, the distinction between ESG funds and social impact funds remains ambiguous in the market. This could stem from the use of ESG ratings as a multifaceted tool serving various investor objectives. While some investors employ ESG for risk management purposes, others use it to enhance their standing in sustainable finance and align with societal and impact concerns.

By 2021, one-third of professionally managed assets, or almost US$30 trillion, were subject to ESG criteria (Howard-Grenville 2021). Globally, ESG assets are set to reach US$53 trillion by 2025 (Bloomberg Intelligence 2021). While Europe and the United States have had the lead in global ESG ETFb37c49d74700 assets, the next wave of growth could come from Asia, specifically from Japan (Bloomberg Intelligence 2021).

Incentives and disincentives for ESG practices

Incentives

From a business perspective there are several incentives for using ESG practices in investing, strategy and disclosure, including but not limited to:

Good behaviour tends to be good for business: companies that effectively handle ESG concerns are inclined to provide better financial performance over an extended period (Sustainalytics 2022b: 5).

A comprehensive review of 60 studies, encompassing over 3,700 study results from more than 2,200 unique primary studies, provides strong evidence supporting the business case for ESG investing. Nearly 90% of the studies analysed demonstrated a positive correlation between ESG factors and corporate financial performance. This enduring positive influence persists, and promising discoveries arise when scrutinising both portfolio and non-portfolio investigations, diverse geographical areas and nascent investment categories such as corporate bonds and environmentally sustainable real estate (Friede, Busch and Bassen 2015: 226-227).

Moreover, in contrast to conventional forms of business risk, social, environmental and governance risks can have a protracted timeline, impacting business on multiple fronts. Countering such challenges would require longer-term capacity building and developing adaptive strategies that can be shaped by ESG considerations (Whelan and Fink 2016).

While the dangers of greenwashing are addressed in further detail later in the document, it is worth noting here that, robust ESG reporting can be “an effective way to demonstrate that [companies] meeting [sustainability] goals and that ESG projects are genuine — not just greenwashing, empty promises, or lip service” (Tocchini and Cafagna 2022).

Investments, partnerships and collaboration: exhibiting a robust dedication towards ESG considerations may provide a strategic advantage to enterprises in the financial markets, given the growing emphasis of investors on sustainability and ethical conduct while making investment choices (Brown and Nuttall 2022).

Here it ought to be noted the role that governments play not just from a policy standpoint but as “the biggest user of capital markets in the emerging markets” via the issuance of sovereign bonds (IFC 2018). Thus, political or regulatory leadership is essential to promoting systematic ESG reporting in such contexts (IFC 2018).

Conversely, ESG reporting can contribute to healthier capital markets. This is due to the fact that high standards of disclosure and transparency mitigate a portion of the risk associated with investing in the most challenging countries, where public institutions and governance are often weak, corruption levels could be high and businesses tend to be smaller (IFC 2018).

Further, ESG is becoming a pivotal constituent of the investment process, along with returns and risk management (Topbas 2022). For instance, the African Development Bank (AfDB) has integrated ESG considerations into its operations through its integrated safeguard system, which is designed to meet international ESG standards by promoting environmental sustainability and improving social conditions (AfDB 2022).

Serving investor interests: according to the PwC 2021 global investor ESG survey, ESG is now a deciding factor for prominent investors worldwide. Nearly half of investors surveyed (49%) are willing to divest from companies that do not adequately address ESG issues. Meanwhile, 83% of those surveyed said that it is important for ESG reporting to give specific information about how ESG goals are being met (PwC 2021).

This trend is set to rise. For instance, Morgan Stanley (2017) found that 86% of millennials were interested in sustainable investing or investing in profitable companies with positive social and environmental impacts. The study also found that millennials were twice as likely as other investors to invest in companies with social or environmental goals, and that 72% of gen Z09e59b7f4822 thought that responsible investment could improve sustainability.

Access to public contracts: the integration of sustainable practices has become crucial in the contemporary business environment, particularly in the context of securing public contracts, thereby promoting sustainable business models (Brown and Nuttall 2022). The inclusion of ESG criteria in public tenders is becoming more common (Acciona 2020). In a recent public-private infrastructure project in Long Beach, California, the selection process for participating for-profit companies involved a screening procedure that assessed their sustainability track record (Henisz, Koller and Nuttal 2019: 3).

Thus, companies that implement environmentally sustainable and socially conscious strategies could be more prone to securing governmental bids and projects (Brown and Nuttall 2022).

Improved reputation and trust: transparency around the societal impact of an organisation's operations and initiatives can lead to trust with regulators and consumers alike, fostering a more conducive business environment (Brown and Nuttall 2022). However, OECD (Boffo and Patalano: 12) cautions that the extent to which current ESG practices sufficiently uncover material information that is accessible and effectively used by investors remains an open question at the present time.

Enhanced resource efficiency: implementing green and more robust supply chains could help businesses to be more resource efficient. Businesses can thus function better by eliminating redundancy and waste and have more cost-effective operations (Brown and Nuttall 2022). Moreover, ESG reporting and disclosure practices can be beneficial for companies’ operational understanding. For instance, if a corporation employs underage workers during its production supply chains or engages in bribery for attaining contracts, it is probable that the firm will encounter harm to its reputation in the event that such information becomes known to consumers. Consequently, this could result in a reduction in revenue generation and subpar financial outcomes

(Faust 2021).

The G, of ESG, dealing with governance could especially help managing corruption risks, reducing legal risks, operational risks, fiduciary risks, security risks (KPMG 2021: 10; Gorely 2022; Lev 2022).

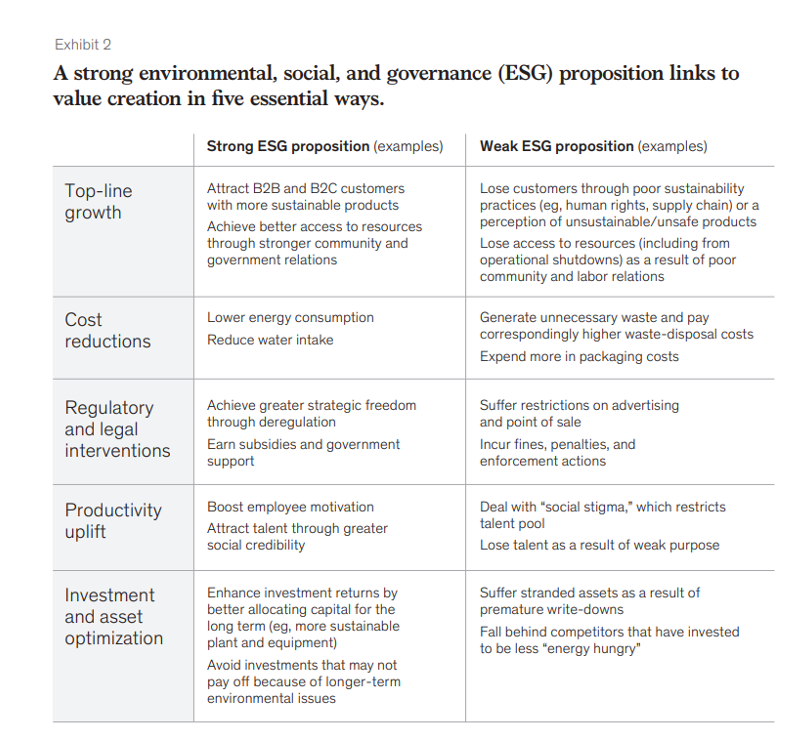

Figure 1: A report by McKinsey Quarterly highlights five ways in which ESG criteria could be beneficial to companies' overall performance.

Source: Henisz, Koller and Nuttall (2019: 4).

Disincentives

Despite the strong market and regulatory demands for ESG practices, businesses face noteworthy challenges and disincentives, including but not limited to:

Short term costs: implementation and adherence to ambitious and tangible ESG standards will inevitably incur a substantial cost, particularly in the short term (Oosterhoff 2022). However, it is worth noting that the costs of not implementing ESG strategies might be higher in the long run. For example, according to a study conducted by Bank of America in 2019, companies listed on the S&P 500 that experienced controversies related to ESG issues since 2014 have collectively witnessed a decline in their stock market values by an estimated US$534 billion. Instances of climate change scandals, allegations of sexual harassment and significant data breaches are among the ESG challenges that have adversely affected the financial worth of corporations (CMS Legal 2023). Among these issues, according to a report by the World Economic Forum (2022: 3, 5), corruption, including bribery, fraud, money laundering, and other illicit financial activities, is a material concern for all corporations and industry sectors. It can substantially affect the worth and future prospects of a company, leading to significant financial loss, reputational damage, market exclusion and even bankruptcy.

Lack of standardisation: there is a significant need for dependable and verifiable ESG data accessibility for both public and private enterprises. Currently, a key challenge is the absence of consistency among various ratings systems, resulting in investors and consumers encountering difficulties in assessing the trustworthiness of these systems. The regulatory oversight of the ratings environment is generally lacking, with numerous frameworks offered by a multitude of providers (McDaniel et al. 2022). Moreover, when it comes to the nature of information being disclosed, institutional investors assert that ESG information offered by corporations is often insufficiently available and of poor quality, making investment decisions more difficult (Ilhan et al. 2019; Hassani and Bahini 2022: 7; Krueger et al. 2023: 1).

In the context of the European Union, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), as an outcome of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) which came into force in January 2023, could set a global example for harmonising reporting practices on ESG criteria to avoid ongoing situations of information asymmetry.

Risk of greenwashing, misrepresentations and ensuing sanctions:the term “greenwashing” pertains to the use of deceptive or misleading information to amplify the perceived environmental benefits of a product, service or organisation. The action in question may be either inadvertent or purposeful. The increasing number of ESG investments has led to a potential hazard of heightened risks of greenwashing. However, it is important to note that greenwashing carries with it a break of trust which could “affect not only those accused of greenwashing but the industry [that the organisation belongs to] as a whole” (Davidson 2022).

In 2021, European antitrust authorities found that Germany's three biggest carmakers illegally colluded to make their emissions technology less effective, leading to higher levels of diesel pollution. While Volkswagen and its Porsche and Audi subsidiaries were levied a fine of €500 million (US$590 million), BMW will have to pay €373 million (US$442 million).

However, greenwashing, while significant is not the only risk that comes with misrepresentation of ESG practices. Companies engaging in reputation laundering or integrity washing with ESG may face risks related to such misleading disclosures, potentially leading to financial crimes like money laundering and fraud by exploiting weaknesses in ESG policies (Deloitte 2023)

Goldman Sachs Asset Management (GSAM) was fined US$4 million by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for ESG violations related to failures in policies and procedures governing ESG factors in their investments (Hannay 2022). The SEC found that GSAM marketed multiple funds as ESG investments without adopting written policies on evaluating ESG factors until after the strategy was introduced. Even after adopting them in June 2018, they failed to consistently follow these policies until February 2020 (Hannay 2022; NY Times 2022).

Other high-profile cases include that of Deutsche Bank’s DWS, which was fined US$25 million for misstatements regarding their ESG measures and failures in policies designed to prevent money laundering (Prentice 2023).

It might be worth noting that ESG considerations may necessitate costly structural modifications, whereas relying on sustainability reporting deficiencies (limited standardisation, for instance) can be profitable. In addition, incentives for companies to report corruption issues may be counterproductive or even pose a legal risk (Yelland 2022; Camacho 2022: 11).

Evidence of ESG affecting corruption

Anti-corruption is crucial not only for G but also for E and S in ESG

Studies highlight the crucial role of governance, particularly anti-corruption measures, within the broader ESG framework. Van de Wijs and van der Lugt (2020: 27) found that among 600 sustainability reporting provisions, a significant portion (349) focused solely on governance themes, with “accountability, anti-corruption and anti-competitive behaviour” receiving the most attention (van de Wijs and van der Lugt 2020: 13). This emphasis underscores the perspective of the World Economic Forum (WEF 2022: 7), which views corporate integrity and anti-corruption practices not just as a component of governance but as “cross-cutting material concern[s] fundamental to the realization of the ESG agenda”. This signifies that corruption not only undermines environmental and social priorities (E and S) but can also distort the entire ESG administration and reporting processes.

However, it ought to be mentioned that, despite its importance and prevalence in reporting provisions, corruption is not consistently considered among asset owners, investment managers and rating agencies in the context of ESG. Inconsistent terminology, framing, reporting recommendations and an overemphasis on environmental issues all contribute to the marginalisation of corruption risks within ESG. These factors impede the effective incorporation of corruption considerations into ESG investing and highlight the need for more consistent and comprehensive approaches to curbing corruption within ESG frameworks (WEF 2022: 3, 11-12).

In fact, corruption can impede proper ESG disclosure as well. A study exploring the relationship between political corruption, carbon risk and voluntary ESG disclosure in US-listed firms between 2005 to 2018 found that political corruption influences the extent of voluntary ESG disclosure. In particular, firms with larger carbon emissions, or “heavy polluters”, profit from local corruption and are less likely to publish their ESG performance voluntarily than their counterparts (Hoang 2022).

Firms’ anti-corruption disclosures are not merely “cheap talk” but reflect actual efforts to address corruption, an analysis of Transparency International’s ratings of self-reported anti-corruption efforts reports (Healy and Serafeim 2016). While ratings are influenced by factors such as enforcement and monitoring, country and industry corruption risk, and governance variables, firms with lower ratings are more likely to be cited in corruption news events, indicating a correlation between their disclosures and real-world corruption issues (Healy and Serafeim 2016). Moreover, such companies tend to report higher future sales growth and experience a negative relationship between profitability change and sales growth in high corruption areas (Healy and Serafeim 2016).

Homing in on anti-corruption could also help with avoiding internal contradictions within ESG reporting by, for instance, having environmentally conscious businesses relying on poorly governed supply chains. Corruption has a significant impact on social considerations within business operations as well. For example, sextortion,c94aeb2de084 a gendered form of corruption, ought to be considered when adequately addressing the issue of sexual harassment. Corruption and human rights abuses and consequent reporting are also linked.

Understanding gaps

Before delving into the potential impact of ESG on anti-corruption efforts, it is crucial to acknowledge the current limitations of ESG metrics in this area. Notably, the inclusion and treatment of anti-corruption and anti-fraud topics vary significantly across different ESG frameworks.

Please refer to Anti-corruption in ESG standards (2022) for a detailed overview of the relevant voluntary standards and how they incorporate anti-corruption issues.

Second, there is the materiality issue. Corruption is understood as a material topic in various ESG standards. For instance, the Global Reporting Index (GRI) considers anti-corruption in its guidance on assessing material topics (GRI 3 2021) and treats as an independent topic standard (GRI 205 2016). However, an organisation may, in theory, provide an explanation as to why it believes the information related to corruption is not material and, as a result, not report on it. Alternatively, the organisation could provide other reasons (such as confidentiality, for example) for not releasing the information (GRI 3 2021; Camacho 2022).

Lastly, taking disclosed ESG information at face value without robust third-party verification or adequate assurance could also pose risks. However, as mentioned, the often-qualitative nature of many ESG indicators and the novelty of ESG disclosure requirements make third-party verification challenging (WEF 2022: 7).

Tamimi and Sebastianelli (2017) looked at the state of S&P 500 companies’ transparency by analysing their Bloomberg ESG disclosure scores. They found that, among S&P 500 companies:

- they vary in their level of disclosure across ESG areas, with governance having the highest transparency terms of reporting and accountability and environmental the lowest

- there is significant variability in the disclosure of specific social policies, such as child labour

- there is significant differences in transparency on both the social and governance dimensions across industries and sectors

- large-cap companies have higher ESG disclosure scores compared to mid-cap companies, and governance factors, such as stricter regulations and reporting requirements, greater resources and stronger investor pressure and scrutiny, influence ESG disclosure

- firms with larger boards of directors, more gender diversity, CEO duality and executive compensation linked to ESG scores demonstrate higher ESG disclosure scores

In terms of trends in ESG reporting quantity, quality, and corporate ESG performance in Swedish multinational corporations, an analysis reveals that, while the quality of ESG information has improved, corporate ESG performance has plateaued since around 2015, suggesting a need for a greater focus on improving ESG outcomes rather than solely enhancing reporting regulations (Arvidsson and Dumay 2021).

Looking at the evidence

Due to aforementioned factors including but not limited to contextual differences, regulatory environments and reporting practices, the impact of ESG reporting on anti-corruption can vary. For instance, weak regulatory frameworks and limited enforcement can reduce the efficacy of ESG reporting in countering corruption. Moreover, it is difficult to assess the actual impact of ESG reporting on corruption due to inconsistencies in reporting frameworks and standards across jurisdictions and organisations.

Theoretically, companies with robust anti-corruption measures incorporated into their ESG strategies are more likely to benefit from ESG reporting, whereas those with inadequate governance structures may not experience significant improvements. Thus, inconclusive evidence exists regarding the relationship between ESG reporting and anti-corruption as a result of the limited availability of dependable data and the changing research landscape. The complexity of corruption and contextual factors contribute further to the diversity of findings. Enhancing the efficacy of anti-corruption measures within the ESG ecosystem requires additional research and the enhancement of ESG reporting frameworks.

Moreover, while going through the finding mentioned below, it is important to make the distinction between correlation and causation. While reporting might be connected to reduced corruption, it is important to consider other factors and the direction of influence. Furthermore, curbing corruption is multifaceted and requires a comprehensive approach. This includes fostering strong corporate ethics, implementing robust internal controls and aiming for a broader societal shifts towards transparency, all of which play crucial roles alongside ESG reporting.

Nevertheless, when it comes to the benefits in ESG reporting for anti-corruption, a scan of evidence available in the public domain, reveals various interesting findings.

Business environment plays a role

Cicchiello et al. (2023) undertook a study on the perception of widespread corruption influencing a company's likelihood of reporting on sustainability matters. The study focused on companies in low and middle-income countries in Asia and Africa and found that companies operating in environments seen as highly corrupt are less likely to produce sustainability reports.f2cdc3301ab3 Moreover, regional and sectoral differences exist; for instance, the study found that companies in Asia tend to produce more sustainability reports than those in Africa, and within Asia, companies in agriculture and financial services report most frequently, whereas those in construction and mining report less frequently than their peers (Cicchiello et al. 2023).

This suggests that businesses operating in environments where corruption is widespread may be less inclined to be transparent.

Diversity is a key component

For instance, an analysis of a panel of 23,169 firm-year observations in China from 2010 to 2019, to understand the impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on corporate financial fraud in China by Lia, Chen and Zheng (2019) we find that CSR reduces both the intensity and likelihood of corporate fraud. Specifically, firms with higher CSR activities related to shareholders and social responsibilities exhibit lower levels of corporate fraud. Moreover, they found that female directors, especially female executive directors, strengthen the negative relationship between CSR and corporate fraud intensity. This moderating effect is even more pronounced in firms located in regions with higher gender equality, greater female representation in government, and higher GDP per capita.

Kim, Park and Shin (2022) argue that well-designed ESG frameworks, including practices such as sustainability reporting, prudent cash management and stock option incentives, can counteract the increased likelihood of financial misreporting associated with more “masculine-faced” CEOs. The background to this being, in finance and accounting research, it has been found that male CEOs with more masculine facial features, as indicated by their facial width-to-height ratio (fWHR), exhibit dual effects on corporate outcomes. While on one hand, firms led by more masculine-faced CEOs tend to achieve better financial performance when measured by return on assets (ROA). On the other hand, they also have a higher likelihood of engaging in financial misreporting or corporate fraud.

A first of its kind study from Pakistan that aimed to examine the relationship between board diversity and CSR disclosure found that that gender and national diversities positively contribute to the quality of CSR disclosure, while age diversity has a negative association, suggesting the inclusion of “diverse forces of gender and nationality” to better ESG disclosure (Khan, Khan and Senturk 2019).

Role of business ethics

A recent study by Marzoukiet al., (2023) involving 347 European firms from 2010 to 2020, finds that companies facing higher corruption risks are less likely to engage in ESG reporting. However, the research also reveals that stronger business ethics can positively moderate the relationship between corporate corruption risk and ESG reporting, encouraging companies to maintain transparency even in high-risk environments.

The authors state that this study offers valuable insights for various stakeholders within a company, and that the findings could appeal to investors focused on social responsibility and citizens who demand corporate accountability. Importantly, the study highlights a path for managers in companies with corruption challenges to improve their practices by prioritising transparency in their ESG reporting (Marzouki et al. 2023).

Information exchange helps

Yet another study (Semenova 2023) examines how private information exchange between institutional investor and public companies affects financial and non-financial performance and transparency. To address material incidents among firms included on the MSCI World Index that are owned by Nordic institutional investors, this study used a unique dataset of 326 private reports linked to environmental, social and anti-corruption recommendations. The results show that target companies and matched companies seem to have similar values in terms of sustainability performance and transparency scores in the three years after private reporting began. Unexpected sustainability events lead to a drop in the market value of target companies compared to the MSCI World Index the following year. Thus, this paper gives real-world evidence for the legitimacy of giving private information about sustainability to public companies as part of a bigger disclosure system (Semenova 2023).

Untapped interlinkages between ESG and AFC

A report by the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS 2022), spells out the interdependence of anti-financial crime (AFC) compliance and ESG frameworks. The report states that integrating AFC processes into ESG governance can improve risk management and strategically align objectives for two areas. The paper emphasises the need to consider the impact of financial crime typologies on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and demonstrates how various AFC issues, such as unlawful mining, trafficking and pollution, intersect with various SDGs. The idea is that by incorporating AFC measures into ESG frameworks, financial institutions can improve their ESG ratings and promote an all-encompassing strategy for curbing financial crime and advancing sustainability (ACAMS 2022: 13).

The report also highlights three examples of financial institutions integrating their AFC obligations with ESG commitments (ACAMS 2022: 14):

- Scotiabank: emphasises the importance of countering financial crime as a component of their ESG obligations. They have adopted a methodology that consolidates its initiatives into four fundamental categories, namely environmental action, economic resilience, inclusive society, and leadership and governance. The process of assessing sustainability and ESG characteristics involves the application of filters to scrutinise the engagement of customers, products and services, and other stakeholders (Scotiabank n. d.).

- JPMorgan Chase: its methodology is woven into their business decisions. Commitments, disclosures, risk management and governance processes are all outlined in the strategy. It also has rules that describe concepts, identification areas, prohibited activities, escalation processes and areas of transaction surveillance (JPMorgan Chase & Co. 2021: 3-5).

- Citigroup: it recognises environmental and human rights challenges and requires policies and mitigation strategies throughout its operations, supply chain and client transaction inspections. Citi's environmental and social risk management (ESRM) policy tracks progress and their framework delineates a strategic approach that is closely linked with the organisation's risk appetite and risk management protocols, aimed at preventing or limiting involvement in high-risk sectors and customer segments, such as military equipment, nuclear power and palm oil.

While the reports and studies mentioned above tell a story of ESG having a positive impact on companies’ anti-corruption behaviour, there are some examples showcasing other relationships between anti-corruption and ESG disclosure.

Paradoxical findings to ongoing narratives on market perceptions

For instance, a study of 28 sample companies in Indonesia from 2015 to 2017, found that an increase their ESG disclosure can actually decrease their value, potentially because the market views it as an attempt to justify excessive investment in ESG activities. Additionally, the research finds that anti-corruption disclosures further amplify the negative impact of ESG on a firm’s value. Such findings highlight the “paradox of the role of disclosures in an emerging market context where the high level of disclosures has not gained the trust of market participants” (Nurrizkiana and Adhariani 2020).

Limited capacity for ESG to avert scandals

It is also worth emphasising that ESG analyses may not be accurate in forecasting or averting corporate scandals, according to Utz (2017). Their study reports a temporary decrease in controversy indicators with the announcement of scandals; however, the overall aggregated ESG ratings do not present a clear picture. As a result, the author opines that it is essential for managers and investors to focus on specific ESG assessment indicators rather than relying exclusively on aggregated assessments for understanding a company’s social responsibility practices (Utz 2017).

Increasing emphasis on ESG performance creates a potential incentive for fraudulent behaviour

Yelland (2022) suggests that the increasing pressure on companies to improve their ESG performance creates conditions that could incentivise ESG fraud. The three elements of the classic fraud triangle – pressure, opportunity and rationale – seem to align with the ESG landscape. Companies may face pressure to meet ESG expectations, leading to opportunities for “greenwashing” or manipulating ESG data to enhance their ESG credentials. The lack of common ESG reporting frameworks and checks on data integrity further contribute to the vulnerability to fraud. The author recommends that boards conduct ESG risk assessments, establish robust ESG compliance frameworks and investigate any red flags to address the risks of ESG fraud (Yelland 2022).

ESG disclosure landscapes

Why ESG reporting?

Due to evolving company risks, investor awareness of financial ramifications and the emergence of sustainable investment products, corporate sustainability information is in high demand. European regulations, citizen knowledge, consumer choices and value chain vulnerabilities fuel this desire (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2022).

The idea is that high-quality sustainability reporting benefits companies. As discussed, due to the rise of sustainable investment products, good reporting can improve financial capital availability. Sustainability reporting may identify and help to manage risks and opportunities, promote stakeholder communication and boost reputation. Also, sustainability reporting guidelines would reduce ad hoc demands and offer appropriate and adequate information (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2022).

However, the reality is that many organisations do not disclose material information on sustainability issues, and sustainability information is not comparable or reliable. Companies that are not required to report sustainability information also contribute to the issue. To guarantee accurate data and prevent greenwashing and double counting, a dependable and cost-effective reporting framework is required, along with efficient auditing procedures (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2022).

Voluntary and mandatory mechanisms

The ESG disclosure landscape includes both voluntary and mandatory practices. Companies that choose to disclose information about their ESG performance on a voluntary basis are generally motivated by market pressures, stakeholder demands and a desire to improve reputation and attract investors (Pérez et al. 2022; Yamamoto 2023). This type of disclosure allows companies to communicate their ESG initiatives and progress according to their own preferences and priorities (Yamamoto 2023).

Mandatory ESG disclosure, on the other hand, refers to regulations and reporting requirements established by regulatory authorities or stock exchanges that oblige corporations to disclose specified ESG information. These rules are intended to standardise ESG reporting while also ensuring transparency and accountability (Asif and Searcy 2022).

While voluntary disclosure could, in theory, allow for flexibility and encourages companies to go above and beyond basic criteria, obligatory disclosure maintains a consistent level of ESG reporting across industries and enables company comparison. The interaction between voluntary and required disclosure is influencing the growing landscape of ESG reporting, with stakeholders asking for increased standardisation and consistency in reporting practices.

Aghamolla and An (2023) examine the equilibrium effects of ESG quality disclosure in both voluntary and mandatory regimes and find that “mandating ESG quality disclosure results in over-investment in the sustainable technology. That is, the manager often implements sustainable investment even though this is overall less preferred by shareholders.” This suggests that from the perspective of shareholders, voluntary disclosure can be more efficient for investment than a mandatory regime. However, their results also show that ultimately “mandating ESG disclosure leads to a greater prevalence of sustainable investing”.

According to former acting chair of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Allison Lee, when there is a voluntary framework for disclosure, not all businesses choose to disclose, leading to significant gaps and an uneven playing field. Inconsistencies arise among those who do disclose, making it difficult for investors to compare businesses within and across industries. Additionally, even within a single business, there may be inconsistencies as they choose to disclose different information at different times (Whieldon 2021).

This paper highlights salient features of mandatory ESG frameworks in the European Union and the United States. For an overview of major voluntary frameworks please refer to Anti-corruption in ESG Standards (2022).

European Union – Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS)

Under the current non-financial reporting directive (NFRD), large public-interest companies in the EU, including listed companies, banks, insurance companies and other designated entities, are required to disclose ESG information if they have more than 500 employees. This covers around 11,700 large companies and groups in the EU (European Commission n.d.). However, starting in 2023, the NFRD has been be replaced by a new directive called the corporate sustainability reporting directive (CSRD). The CSRD will expand the scope of companies obligated to comply, including approximately 50,000 companies in the EU, representing 75% of the EU’s total turnover (European Commission n.d.). This includes public companies that engage in commercial activities.

According to the erstwhile NFRD, large private companies had to disclose information on environmental issues, social matters and employee treatment, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery measures, as well as diversity on company boards, considering factors such as age, gender, educational background and professional experience (European Commission n.d.).

As per the now-in-force CSRD, companies meeting two of the following three conditions will have to comply with the new regulations (European Commission n.d.):

- €40 million in net turnover

- €20 million in assets

- 250 or more employees

A few salient features of the CSRD are as follows (Davies et al. 2023; European Parliament and the Council of the European Union 2022):

- Uniform reporting standards: the CSRD introduces uniform reporting standards across the EU through the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), covering various ESG metrics (details follow).

- Double materiality: the CSRD requires companies to consider both the material impacts of ESG factors on the organisation and the organisation’s impacts on the environment and social systems, adopting a “double materiality” perspective. Consequently, companies subject to the CSRDneed to reassess their conceptual approach and allocate appropriate resources to meet the reporting obligations. Notably, this differs from other reporting frameworks, such as those in the United States, which do not adopt the double materiality perspective in their risk assessment processes.

- Third-party assurance: reporting entities are obliged to obtain third-party assurance or audit, with limited assurance from 2025, with the possibility of developing a “reasonable” assurance standard by 2028.

- Reporting mechanisms: companies will report ESG metrics within the company management report, seamlessly integrating sustainability and financial disclosures for a holistic view of the company's performance and impact. Sustainability information will be digitally tagged to maintain a uniform database of CSRD disclosures for increased transparency and accessibility for stakeholders across the globe.

- Applicable to the entire value chain: it includes reporting requirements for companies’ broader value chain, not just their own operations. Companies must report material impacts, risks and opportunities from their direct and indirect business links in the upstream and/or downstream value chain. This extension may lead to considerable ESG data demands from companies outside CSRD. Companies are only obligated to report on “material” entities in the value chain based on double materiality.0bc050f5e223 The EU has granted a three-year grace period for reporting value chain information difficulties. Companies can explain their value chain information efforts and shortcomings during this period.

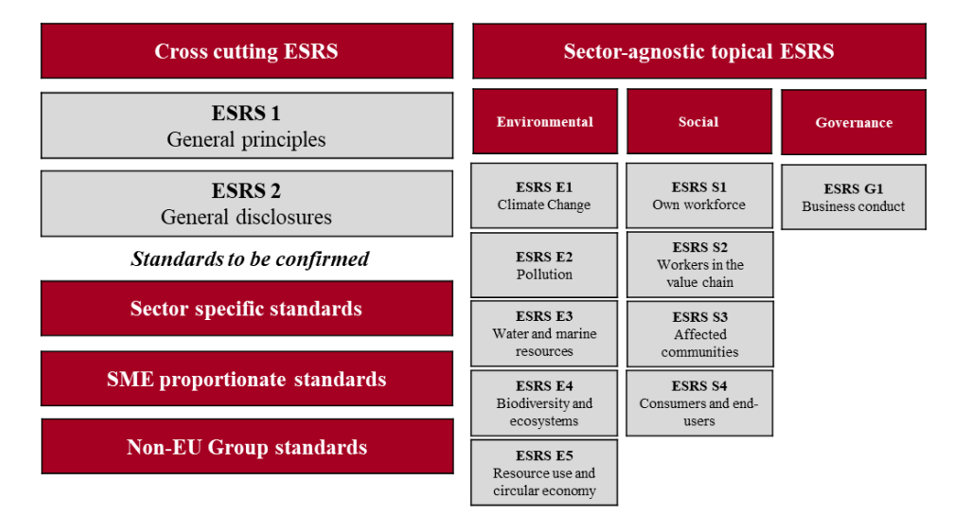

The European Financial Reporting Advisory Group’s (EFRAG) Sustainability Reporting Board (SRB) developed the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). In April 2022 and November 2022, it came out with an exposure draft and a first draft on 12 ESRS respectively. The first set of the ESRS was finalised on 31 July 2023, and published in the Official Journal of the EU on 22 December 2023. This set includes two comprehensive ESRS covering multiple areas and ten ESRS focused on specific topics that are not limited to any particular sector. The ten topical ESRS are further categorised into five environmental ESRS, four social ESRS and one governance ESRS (see Figure 2 below) (EFRAG 2023b; European Commission 2023).

Figure 2: Overview of ESRS.

Source: Davies et al. (2023).

One of the stated objectives of the ESRS G1 on business conduct is to provide an understanding of a company's approach to ethical business practices (EFRAG 2023a). It focuses on (EFRAG 2023a):

- business ethics and corporate culture: this includes anti-corruption and anti-bribery, the protection of whistleblowers, and animal welfare

- supplier relationships: this includes treatment of suppliers, especially focusing on fair and prompt payments, particularly to small and medium enterprises (SMEs)

- political influence: this focuses on company transparency regarding lobbying and other activities and commitments to undertakings related to exerting political influence

It is important to note that the ESRS implement a tiered approach: ESRS 1 establishes general principles for consistent and comprehensive company reporting, while ESRS 2 mandates specific disclosuresc11118d7ee48 on broad sustainability topics for all companies under the CSRD (European Commission 2023).

Subsequent standards and their specific requirements (including ESRS G1) are subject to a materiality assessment, i.e., “the company will report only relevant information and may omit the information in question that is not relevant (‘material’) for its business model and activity” (European Commission 2023).

However, materiality assessments are not voluntary; companies must disclose relevant information and have the process externally assured. This ensures robust reporting of all sustainability information necessary under the CSRD framework. Notably, even if a company deems a specific topic immaterial – for example, climate change – it must provide detailed justification for their assessment, acknowledging its broader systemic significance (European Commission 2023).

ESRS G1 states that the disclosures should be read in conjunction with other ESRS standards for a holistic view of the company's sustainability efforts. In particular, it clarifies that ESRS 2: general requirements3b2e4f64a0df establishes the foundational principles and reporting requirements for all other ESRS standards. This includes essential elements such as governance (GOV), strategy (SBM) and management of impacts, risks and opportunities (IRO) (EFRAG 2023a).

When it comes to the structure of reporting as per ESRS G1, it can be viewed as per this table:

Table 1: Structure of reporting

|

General disclosure requirements |

Implications, risks and opportunities |

Metrics and targets |

|

ESRS 2 GOV-1: |

ESRS 2 IRO-1: |

ESRS G1-4: |

|

|

ESRS G1-1: |

ESRS G1-5: |

|

|

ESRS G1-2: |

ESRS G1-6: |

|

|

ESRS G1-3: |

|

ESRS 2 GOV-1, as a general disclosure requirement mandates reporting on the role of the administrative, management and supervisory bodies. It delineates disclosure of the role of these bodies in relation to business conduct as well as their expertise on the matters of business conduct (EFRAG 2023a). Meanwhile, ESRS 2 IRO-1 mandates that companies describe the process to identify material impacts, risks and opportunities in relation to business conduct matters, as well as “disclose all relevant criteria used in the process, including location, activity, sector and the structure of the transaction” (EFRAG 2023a).

Please see below for the specific disclosure requirements (EFRAG 2023a):

G1-1 Business conduct policies and corporate culture

The aim of this requirement is to understand the company's commitment to ethical practices and its approach to fostering integrity in corporate culture.

Companies are required to disclose on:

- Reporting mechanisms: procedures identifying, reporting and investigating concerns about unethical or illegal behaviour, including breaches of internal codes of conduct. Also stating if such mechanisms “accommodate reporting from internal and/or external stakeholders”.

- Anti-corruption & anti-bribery(as per UNCAC): companies must explicitly state if they lack policies in compliance with the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). If so, they must indicate plans and a timeline for implementing such policies.

- Whistleblower protections:

- outline internal reporting channels, including dedicated reporting hotlines, and whether employee training/information is provided

- detail the process for designating and training staff who will manage whistleblower reports

- specify measures to protect whistleblowers from retaliation, aligning with relevant legislation (e.g., Directive (EU) 2019/1937)

- Incident investigation: beyond procedures to follow-up on reports by whistleblowers, whether companies have procedures to “investigate business conduct incidents, including incidents of corruption and bribery, promptly, independently and objectively”.

- Animal welfare policies (if applicable): disclose policies relating to ethical treatment of animals within the company's operations.

- Employee training: Describe the company's business conduct training programme, specifying the target audience, depth of content and frequency of training sessions.

- High-risk functions: identify internal roles or departments most susceptible to corruption and bribery risks.

G1-2 – Management of relationships with suppliers

The disclosure requirement aims to provide an understanding of how companies manage their procurement process, emphasising fair behaviour towards suppliers.

G1-3 – Prevention and detection of corruption or bribery

Companies are obligated to provide information about their systems for preventing, detecting, investigating and responding to allegations or incidents related to corruption and bribery, including relevant training. The objective of this disclosure requirement is to ensure transparency regarding the key procedures implemented by companies to address corruption and bribery concerns. This includes information on training provided to their employees and internal or supplier communications.

The disclosure must include the following information concerning prevention and detection:

Companies must disclose their internal systems for addressing corruption and bribery. This includes procedures for:

- Prevention and detection: explain the measures used to proactively prevent and uncover potential instances of corruption or bribery.

- Investigation and response: describe how allegations or incidents are investigated and the appropriate responses implemented.

- Reporting and accountability: detail whether investigators are independent of the management chain, and outline how outcomes are reported to governing bodies.

- Training and communication: disclose the type, reach and content of anti-corruption and anti-bribery training programmes. Specify the percentage of high-risk roles covered by the training. Indicate whether training is offered to administrative, management and supervisory bodies.

Companies lacking such systems must explicitly state this fact. If applicable, they should disclose future plans for implementing these procedures.

G1-4 – Confirmed incidents of corruption or bribery

Companies are required to provide information on confirmed incidents of corruption or bribery that occurred during the reporting period. The objective of this disclosure requirement is to ensure transparency regarding such incidents and their outcomes (EFRAG 2023a). It is important to note that within this requirement, some measures are mandatory and some voluntary.

For mandatory measures, it states “the undertaking shall disclose” (EFRAG 2023a):

- The number of convictions for violating anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws, along with the total amount of fines incurred.

- Any actions the company has taken as a consequence of breaches in their anti-corruption and anti-bribery policies and procedures.

Apart from this, companies “may disclose” optionally:

- total number and details of confirmed cases of corruption or bribery

- number of employees dismissed or disciplined due to corruption or bribery incidents

- number of contracts with business partners that were ended or not renewed because of violations related to corruption or bribery

- details of public legal cases against the company and its employees regarding corruption or bribery, including ongoing cases and the outcome of cases concluded during the reporting period

It also clarifies that disclosures of incidents within the company's value chain are only required if the company or its employees were directly involved.

G1-5 – Political influence and lobbying activities

The aim of this disclosure requirement is to increase transparency about the company's political influence and financial contributions. It requires reporting on (EFRAG 2023a):

- Oversight: naming the individuals within the governing bodies responsible for overseeing political influence activities.

- Contributions: reporting the total value of financial and in-kind political contributions (broken down by country or relevant geographic areas and type of recipient). An explanation of how in-kind contribution values are calculated is also required.

- Lobbying activities: delineating the primary topics covered by lobbying efforts and briefly outline the company's major positions on them. Moreover, making clear as to how these lobbying activities align with the company's material impacts, risks and opportunities as identified by their materiality assessment (in line with ESRS 2).

- Transparency registers: if the company is included in the EU transparency register (or a comparable registry in a member state), provide the register name and the company's identification number.

- Revolving doors: detail any appointments of governing body members who held similar positions in public administration (e.g., regulators) within the past two years of the reporting period.

G1-6 – Payment practices

To enhance transparency and address concerns over late payments, companies must disclose details about their payment practices, particularly those impacting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This includes average payment times, standard payment terms for different supplier categories, the percentage of payments adhering to these terms, and the number of legal proceedings for late payments. Additionally, companies may provide further context to clarify their payment practices

The draft ESRS G1 contained a detailed annex providing definitions for bribery, corporate culture, confirmed incidents of corruption or bribery, corruption and lobbying activities (EFRAG 2022b: 9). The finalised ESRS G1 has an annex that offers additional instructions to support companies in making the required disclosures about their business conduct.

However, it is interesting to note that, as per the exposure draft ESRS G2 business conduct, April 2022, that was made available for consultation, beneficial ownership information was a disclosure requirement (Disclosure Requirement G2-8), which aimed to “include information on the identity of who the ultimate beneficial owners or those who control of the undertaking are, together with their respective ownership or control percentages”.

However, the requirement of beneficial ownership disclosure was removed from the current draft ESRS GI Business Conduct, November 2022. The justification given for its removal includes the consideration that the information would be superfluous in the context of public beneficial ownership registers in the EU and the perception of a tenuous link to bribery/corruption, as per the basis of conclusions, March 2023 and the due process note – first set of draft ESRS.

United States

In the US, ESG considerations have historically been driven by voluntary market responses, while the European Union and the United Kingdom have implemented specific directives and regulations on ESG. However, there has been a rapid change in the US regulatory landscape in the past 18 months. The Biden administration issued an executive order to address climate related risks, and the SEC has taken steps to tackle climate change and other ESG risks (Worldfavor 2022; Silk and Lu 2023).

A brief overview of the main ESG disclosure regulations is as follows (Harrington and Garzon 2022; Wolrdfavour 2022; Silk and Lu 2023):

- SEC requires public companies to disclose information that may be material to investors on ESG related risks and sets disclosure expectations.

- A 2020 guidance from the SEC, while not specifically targeting ESG measures or requiring new disclosures, mentions various ESG metrics (such as energy use and employee turnover) as potential examples of key performance indicators (KPIs) that could be incorporated into management's discussion and analysis (MD&A) disclosures.

- The revised Regulation S-K in August 2020 now includes a requirement for companies to provide descriptions of their “human capital resources” if they are material to understanding the business. It also calls for the disclosure of any human capital measures or objectives that the company focuses on in managing its business, which may include areas such as personnel development, attraction and retention.

- Nasdaq rules implemented in 2021 require listed companies to have diverse directors and disclose self-identified gender, racial characteristics and LGBTQ+ status of their boards. While the rule is still in existence, it is the subject of a pending lawsuit to overturn it on constitutional and statutory grounds.

- The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) updated the climate risk disclosure survey to align with TCFD standards for insurance companies.

- Rule 14a-8 of the Exchange Act has been used by shareholders to propose ESG disclosures. ESG proposals, particularly those connected to climate risks and diversity, equity and inclusion, increased in the 2022 proxy season due to SEC guidance that limited firms’ ability to exclude them.

- The SEC has proposed amendments to Regulations S-K and S-X that would require companies to disclose climate related risks and opportunities. The proposed rules would expand upon the SEC’s previous guidance from 2010 and cover areas such as board and management oversight, greenhouse gas emissions, the impact of climate events on financial statements, and climate related targets and goals. The rules would be phased in over three years, with larger filers facing additional requirements for third-party attestation.

- Climate related disclosures would be subject to liability provisions under the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

- The SEC is expected to release additional proposed rules on human capital, board diversity and cybersecurity disclosures.

- Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are pooled investment security traded on exchanges and typically designed to mirror the performance of a specific index (Chen 2023).

- Generation Z comprises people born between 1996 and 2010.

- Sextortion as defined by the International Association of Women Judges (IAWJ) is “a form of sexual exploitation and corruption that occurs when people in positions of authority … seek to extort sexual favours in exchange for something within their power to grant or withhold. In effect, sextortion is a form of corruption in which sex, rather than money, is the currency of the bribe” (IBA n.d.).

- It is important to note that these jurisdictions do not have mandatory ESG reporting as yet.

- This means that companies do not have to report on every entity within their entire supply chain (upstream and downstream). Instead, they only need to report on those entities that are considered “material” according to the “double materiality” principle.

- Irrespective of which sustainability matter is being considered.

- ESRS 2 defines basic disclosure contests for every standard, in particular processes and methodologies to collect the required data and information.